RACING CARS FROM THE SIXTIES

Jaguar XJR-5 - 1969

USA

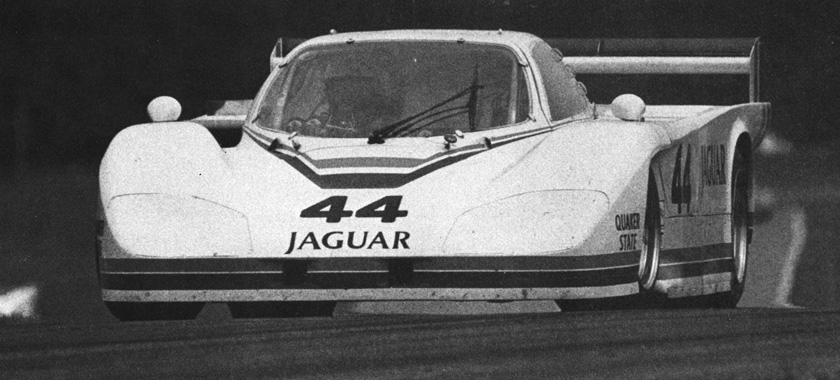

AT THE END of the 1983 racing season when IMSA totals up all of the points accrued by its Camel GT competitors, guess which marque may win the GTP manufacturers championship? Porsche? Could be. Chevrolet? Perhaps. Personally, I wouldn't be surprised if it is Jaguar whose sleek XJR-5 coupe has won two IMSA contests in its first full season of racing. The Jaguar is unique, not just because it is the only entry to use Coventry's lion-hearted sohc V -12, but because its body/chassis is a one-of-a-kind design conceived and built in America by Americans. Hands across the water, circa 1983.

All ribbing aside, this Anglo-American marriage is an old and lasting relationship that involves Group 44 Inc and the parent company, presently known as Jaguar Cars Inc. Not too long ago the British firm was known as Jaguar-Rover-Triumph and before that, British Leyland. Group 44, on the other hand, has been known 'as Group 44 for as long as Bob Tullius and company have been building and racing English cars- 20 years to be exact. During that period, the cars of Group 44, everything from Triumph Spitfires to the elegant XJS Trans-Am racer, have won 13 national titles and three Trans-Am championships.

Bob.and Group 44 are no strangers to R&T and in previous years we have tested their TR7, TR8 and Jaguar XJ-S. But the XJR-5 is a different breed of cat because these days professional racing, Camel GT style, is different. 'Grand Touring Experimental (GTX) racers such as the Porsche 935 Turbos are being replaced by Grand Touring Prototypes (GTPs) such as the March-Porsche and Lola-Chevrolet as star attractions.

Readers may recall a Sam Posey insightful article, "Fast Company: Driving the Lola T-600," that appeared in March 1982. It was our introduction to this new generation of 'race cars, which rely on ground:.effect magic for their incredible handling. The Lola was quite remarkable in its day and Brian Redman won overall honors in the 1981 Camel GT championship driving the Chevrolet-powered racer. But time marches on and so does the state of the art, one reason we accepted Bob's offer to test the XJR-5. The other reason is that the car is a Jaguar - sort of. You'll see what I mean as our story unfolds.

Chapter One: It is 1980 and Group 44 is facing a bleak future. Triumph will cease production at the end of the year and the TR8 Bob and Bill Adam have been racing in the Camel GT championship will no longer have any value as a promotional tooL Unemployment seems imminent when Tullius and Mike Dale; JRT of North America's Vice President of Sales and Marketing are summoned, to Coventry, England, by John Egan, Jaguar's Managing Director. Egan tells them that the company would like to revitalize its performance image beginning with a North American racing program. It is decided that the Camel GT is the arena in which a new Jaguar racer will compete. It will be a prototype not a silhouette such as the Porsche 935, because this is the direction the Camel GT and Europe's World Endurance Manufacturers Championship are headed. Furthermore, Egan insists that the racer will be a Jaguar, not just a Lola or March with a Jag engine. And it will be a universal design conforming to both IMSA and FISA regulations and capable of competing in either series. A timetable is laid out. First year (1981): Race the XJ-S in the SCCA Trans-Am while building the GTP. Second year: Race test the GTP. Third year: Participate in the GT fulltime and strive to win the championship.

Chapter Two: Tullius returns to the U.S. and looks for a designer. He chooses Lee Dykstra, not just because ,he has a good track record (IMSA Chevrolet Monzas, Al Holbert's Can-Am racers), but because he knows suspension and aerodynamics. Besides, he is an old friend. Lee builds a one-quarter scale clay model and tests it in the University of Michigan wind tunnel. He follows up with a full-scale clay of the body and tests that at the Lockheed tunnel in Marietta, Georgia. The design is an aerodynamic winner. Dykstra starts cranking out blueprints and sending them to Group 44's Winchester, Virginia workshops. The crew begins fabricating and assembling the car. Later, Tullius explains how difficult it was. "For the first time we had to build a race car from scratch and we didn't know the relationship of one piece to another." Nevertheless, they persevere and on June 15, 1982, the XJR-5 rolls out of the shop.

Chapter Three: Life in the fast lane begins. The car runs well "right out of the box," and in its first race at Road America in August 1982, it finishes 3rd. unfortunately, a spate of bad luck follows. A crash at Mid-Ohio destroys the only chassis and prevents the team from competing at Road Atlanta. At Pocono, an engine problem sidelines the new car while it is running 3rd. In the Camel GT finale at Daytona, the right rear tire blows while Tullius is about to take over 3rd place. The car slams into the wall and is destroyed. .

Chapter Four: Group 44 has spent the winter (a scant two months) building a new car. The bodywork has been refined somewhat, but the basic design remains unchanged.

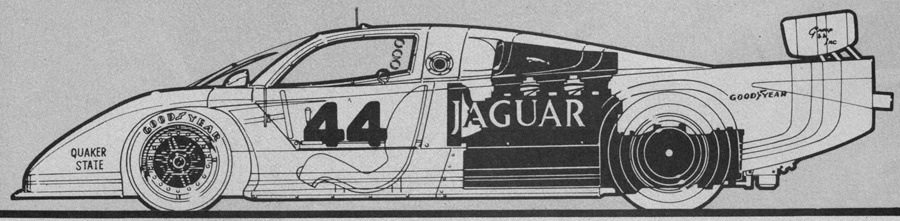

An aluminum monocoque tub serves as the nucleus for the chassis/body, which has a tubular steel rollcage and Kevlar body sections. Many of these pieces such as the nose, the sidepods, the doors and the tail are removable. The rest of the Kevlar components are not and make up the basic structure of the car. The ground-effect tunnels (venturi) begin just behind the cockpit and sweep upward to the car's trailing edge. They skirt the sides of the engine, which serves as a stressed member. The rear suspension crosspiece bolts to the block and to the Hewland VGDG 600 gearbox that hangs out past the rear axle. .

The XJR-5's suspension is also pretty conventional. There are none of the push/pull rods seen in Formula I and Can-Am cars: Instead, the Jag uses coil springs with internally mounted shocks supporting upper and lower A-arms at all four corners. Front and rear anti-roll bars (adjustable externally but only at the rear) and 13-in. diameter outboard-mounted Lockheed disc brakes round out the suspension package. .

The Jag's cockpit is stark, an aluminum room with a Kevlar ceiling. The driver's bucket seat is on the right because most road courses are run in a clockwise-direction. The shifter is also on the right because most drivers of the western world are accus~ tomed to this location. Spread out at the base of the windshield is the dashboard. It's dominated by a large Jones Motrola mechanical tachometer. Tullius distrusts electronic tachs ever since the one used in 1982 proved to be inaccurate and (says Bob) led to the XJR-5's engine failure at Pocono. Strung out to eifher side of the rev counter are engine oil and coolant temperature gauges, ammeter, plus fuel and oil pressure gauges.

So far, there seems to be little evidence of anything Jaguar in the XJR-5. But there is. The engine block, cylinder heads and crankshafts are Coventry's own even though most of the remaining components are V.S. aftermarket parts and include Jet titanium connecting rods, Forged true pistons, and Crane camshafts. In this day of fuel injection, turbocharging and sophisticated engine controls, the Jag powerplant seems almost archaic with its sextet of dual-throat Weber 48 IDA carburetors. Not to worry, because as rudimentary as the setup may appear, it still enables the 364-cu-in. V-12 to pump out a healthy 575 bhp and develop an impressive 480 Ib-ft of torque.

Chapter Five: Group 44 meets us at Road Atlanta. The team is en route to Daytona, but tarries a bit so that Engineering Editor Dennis Simanaitis and I can put the XJR-5 through its paces. But things are less than ideal. The weather is cold with a threat of rain. And the Jag's final drive is a 2.58:l, one of the team's tallest ratios. Of course-the XJR-5 is set up for the sustained high speeds of Daytona. But, by comparison, in our most recent look at a racer (the Electramotive Datsun ZX Turbo, May 1983), that car was geared for quarter-mile acceleration with a 4.41: I final drive. .

Bob tries a few quarter-mile runs from a standing start, but it's clear the big cat is barely clearing its throat as it roars past the 500-ft point. Later, we do some analyses of speeds in gears, and it's no wonder the Jag objects to this treatment: Its 1st gear is good for 77 mph, just 2 mph less than the ZX racer's 2nd; and the Jag's 3rd-gear limit of 144 mph is almost spot on with the ZX's 5th. We can only speculate as to the Jag's acceleration potential in short-track trim, but note that it's carrying 4.2 Ib/bhp compared to the ZX racer's 4.6, and this latter car got to 60 in 3.8 seconds and posted quarter-mile results of 11.5 sec at 131 mph. .

Conditions for the panic stop portion of our testing are also less than ideal. GTP cars rarely make U-turns, as you might guess. and the XJR-5 needs more width than that available along Road Atlanta's back straight. So Bob runs laps of the 2.5mile circuit and tries to heat the brakes and tires as he slows to 60 or 80 mph for our measurements. Nothing gets very warm on this particular da. and the car's 107 ft from 60 is disappointing.

Then Bob gets the hang of it and pulls out several stops from 80 in the vicinity of 146 ft. This is more like it, as the huge 13.0-in. discs respond to harder use and the tires' grip improves as downforce increases.

Then Bill Adam. Bob's co-driver, takes over to drive the Jag through our handling evaluations. Although Bill is new to our slalom. he quickly hones in threading the 79.0-in. wide racer through the cones. His best run is an astoundingly quick 68.3 mph. right up there with our current race car record of 68.5 mph (held by the Lancia Group 5 Turbo). We try setting up a skidpad. but the firmly suspended ground-effect machine just bounds from high point to high point of the less than perfect surface. No matter; it's clear from the super-quick slalom that this big cat handles with the best of racers.

With the completion of formal testing. Tullius suggests that I try the Jaguar on for size. It doesn't fit all that well because Bob and Bill are around 6 ft tall and I am 5 ft 5 in. Nevertheless, I make the sacrifice and with toes barely touching the pedals. coax the car onto the circuit. At slow speeds the steering is - heavy and quick and it takes some doing to keep from weaving down the track. But as I adjust to the car and pick up speed. the steering improves, getting lighter and precise. I go faster and realize that the car sticks to the pavement, partially because of its ground-effect design, which is just beginning to work, but mostly because of its suspension and those very wide Goodyear tires. On occasion, I hesitate going into a turn and the car feels loose. But a blast of power plants its tires firmly on the roadway and sends the car scurrying off to the next turn. At times like this I'm aware of the engine's excellent mid-range torque and its flexibility. And its noise, which reaches 115 dBA at redline. With each lap I gain confidence in the Jag's handling and although I do not reach the car's-nor my-potential, I'm convinced that I could do so. Perhaps some other time when I've been fitted to the car and when the Camel GT championship is not at stake.

Chapter Six: It is midway through the 1983 IMSA season and the Jaguar has finally hit its stride. Although. Daytona is another disaster-a suspension part breaks and sends. the car into the guardrail-and Miami and Sebring are nothing to shout about, it all comes together at Road Atlanta where the Jag wins. At Riverside, Adam hits a patch of oily roadway and crashes. But at Laguna Seca and Charlotte, the XJR-5 is 2nd and 3rd respectively. By Lime Rock, it's back on top with another Camel GT victory. End of story, but certainly not the conclusion of the Jaguar XJR-5's adventures and the team's quest for the Camel GT championship. If Bob Tullius, Bill Adam and Group 44 succeed, 1983 could go down as the year of the cat in IMSA annals.

All ribbing aside, this Anglo-American marriage is an old and lasting relationship that involves Group 44 Inc and the parent company, presently known as Jaguar Cars Inc. Not too long ago the British firm was known as Jaguar-Rover-Triumph and before that, British Leyland. Group 44, on the other hand, has been known 'as Group 44 for as long as Bob Tullius and company have been building and racing English cars- 20 years to be exact. During that period, the cars of Group 44, everything from Triumph Spitfires to the elegant XJS Trans-Am racer, have won 13 national titles and three Trans-Am championships.

Bob.and Group 44 are no strangers to R&T and in previous years we have tested their TR7, TR8 and Jaguar XJ-S. But the XJR-5 is a different breed of cat because these days professional racing, Camel GT style, is different. 'Grand Touring Experimental (GTX) racers such as the Porsche 935 Turbos are being replaced by Grand Touring Prototypes (GTPs) such as the March-Porsche and Lola-Chevrolet as star attractions.

Readers may recall a Sam Posey insightful article, "Fast Company: Driving the Lola T-600," that appeared in March 1982. It was our introduction to this new generation of 'race cars, which rely on ground:.effect magic for their incredible handling. The Lola was quite remarkable in its day and Brian Redman won overall honors in the 1981 Camel GT championship driving the Chevrolet-powered racer. But time marches on and so does the state of the art, one reason we accepted Bob's offer to test the XJR-5. The other reason is that the car is a Jaguar - sort of. You'll see what I mean as our story unfolds.

Chapter One: It is 1980 and Group 44 is facing a bleak future. Triumph will cease production at the end of the year and the TR8 Bob and Bill Adam have been racing in the Camel GT championship will no longer have any value as a promotional tooL Unemployment seems imminent when Tullius and Mike Dale; JRT of North America's Vice President of Sales and Marketing are summoned, to Coventry, England, by John Egan, Jaguar's Managing Director. Egan tells them that the company would like to revitalize its performance image beginning with a North American racing program. It is decided that the Camel GT is the arena in which a new Jaguar racer will compete. It will be a prototype not a silhouette such as the Porsche 935, because this is the direction the Camel GT and Europe's World Endurance Manufacturers Championship are headed. Furthermore, Egan insists that the racer will be a Jaguar, not just a Lola or March with a Jag engine. And it will be a universal design conforming to both IMSA and FISA regulations and capable of competing in either series. A timetable is laid out. First year (1981): Race the XJ-S in the SCCA Trans-Am while building the GTP. Second year: Race test the GTP. Third year: Participate in the GT fulltime and strive to win the championship.

Chapter Two: Tullius returns to the U.S. and looks for a designer. He chooses Lee Dykstra, not just because ,he has a good track record (IMSA Chevrolet Monzas, Al Holbert's Can-Am racers), but because he knows suspension and aerodynamics. Besides, he is an old friend. Lee builds a one-quarter scale clay model and tests it in the University of Michigan wind tunnel. He follows up with a full-scale clay of the body and tests that at the Lockheed tunnel in Marietta, Georgia. The design is an aerodynamic winner. Dykstra starts cranking out blueprints and sending them to Group 44's Winchester, Virginia workshops. The crew begins fabricating and assembling the car. Later, Tullius explains how difficult it was. "For the first time we had to build a race car from scratch and we didn't know the relationship of one piece to another." Nevertheless, they persevere and on June 15, 1982, the XJR-5 rolls out of the shop.

Chapter Three: Life in the fast lane begins. The car runs well "right out of the box," and in its first race at Road America in August 1982, it finishes 3rd. unfortunately, a spate of bad luck follows. A crash at Mid-Ohio destroys the only chassis and prevents the team from competing at Road Atlanta. At Pocono, an engine problem sidelines the new car while it is running 3rd. In the Camel GT finale at Daytona, the right rear tire blows while Tullius is about to take over 3rd place. The car slams into the wall and is destroyed. .

Chapter Four: Group 44 has spent the winter (a scant two months) building a new car. The bodywork has been refined somewhat, but the basic design remains unchanged.

An aluminum monocoque tub serves as the nucleus for the chassis/body, which has a tubular steel rollcage and Kevlar body sections. Many of these pieces such as the nose, the sidepods, the doors and the tail are removable. The rest of the Kevlar components are not and make up the basic structure of the car. The ground-effect tunnels (venturi) begin just behind the cockpit and sweep upward to the car's trailing edge. They skirt the sides of the engine, which serves as a stressed member. The rear suspension crosspiece bolts to the block and to the Hewland VGDG 600 gearbox that hangs out past the rear axle. .

The XJR-5's suspension is also pretty conventional. There are none of the push/pull rods seen in Formula I and Can-Am cars: Instead, the Jag uses coil springs with internally mounted shocks supporting upper and lower A-arms at all four corners. Front and rear anti-roll bars (adjustable externally but only at the rear) and 13-in. diameter outboard-mounted Lockheed disc brakes round out the suspension package. .

The Jag's cockpit is stark, an aluminum room with a Kevlar ceiling. The driver's bucket seat is on the right because most road courses are run in a clockwise-direction. The shifter is also on the right because most drivers of the western world are accus~ tomed to this location. Spread out at the base of the windshield is the dashboard. It's dominated by a large Jones Motrola mechanical tachometer. Tullius distrusts electronic tachs ever since the one used in 1982 proved to be inaccurate and (says Bob) led to the XJR-5's engine failure at Pocono. Strung out to eifher side of the rev counter are engine oil and coolant temperature gauges, ammeter, plus fuel and oil pressure gauges.

So far, there seems to be little evidence of anything Jaguar in the XJR-5. But there is. The engine block, cylinder heads and crankshafts are Coventry's own even though most of the remaining components are V.S. aftermarket parts and include Jet titanium connecting rods, Forged true pistons, and Crane camshafts. In this day of fuel injection, turbocharging and sophisticated engine controls, the Jag powerplant seems almost archaic with its sextet of dual-throat Weber 48 IDA carburetors. Not to worry, because as rudimentary as the setup may appear, it still enables the 364-cu-in. V-12 to pump out a healthy 575 bhp and develop an impressive 480 Ib-ft of torque.

Chapter Five: Group 44 meets us at Road Atlanta. The team is en route to Daytona, but tarries a bit so that Engineering Editor Dennis Simanaitis and I can put the XJR-5 through its paces. But things are less than ideal. The weather is cold with a threat of rain. And the Jag's final drive is a 2.58:l, one of the team's tallest ratios. Of course-the XJR-5 is set up for the sustained high speeds of Daytona. But, by comparison, in our most recent look at a racer (the Electramotive Datsun ZX Turbo, May 1983), that car was geared for quarter-mile acceleration with a 4.41: I final drive. .

Bob tries a few quarter-mile runs from a standing start, but it's clear the big cat is barely clearing its throat as it roars past the 500-ft point. Later, we do some analyses of speeds in gears, and it's no wonder the Jag objects to this treatment: Its 1st gear is good for 77 mph, just 2 mph less than the ZX racer's 2nd; and the Jag's 3rd-gear limit of 144 mph is almost spot on with the ZX's 5th. We can only speculate as to the Jag's acceleration potential in short-track trim, but note that it's carrying 4.2 Ib/bhp compared to the ZX racer's 4.6, and this latter car got to 60 in 3.8 seconds and posted quarter-mile results of 11.5 sec at 131 mph. .

Conditions for the panic stop portion of our testing are also less than ideal. GTP cars rarely make U-turns, as you might guess. and the XJR-5 needs more width than that available along Road Atlanta's back straight. So Bob runs laps of the 2.5mile circuit and tries to heat the brakes and tires as he slows to 60 or 80 mph for our measurements. Nothing gets very warm on this particular da. and the car's 107 ft from 60 is disappointing.

Then Bob gets the hang of it and pulls out several stops from 80 in the vicinity of 146 ft. This is more like it, as the huge 13.0-in. discs respond to harder use and the tires' grip improves as downforce increases.

Then Bill Adam. Bob's co-driver, takes over to drive the Jag through our handling evaluations. Although Bill is new to our slalom. he quickly hones in threading the 79.0-in. wide racer through the cones. His best run is an astoundingly quick 68.3 mph. right up there with our current race car record of 68.5 mph (held by the Lancia Group 5 Turbo). We try setting up a skidpad. but the firmly suspended ground-effect machine just bounds from high point to high point of the less than perfect surface. No matter; it's clear from the super-quick slalom that this big cat handles with the best of racers.

With the completion of formal testing. Tullius suggests that I try the Jaguar on for size. It doesn't fit all that well because Bob and Bill are around 6 ft tall and I am 5 ft 5 in. Nevertheless, I make the sacrifice and with toes barely touching the pedals. coax the car onto the circuit. At slow speeds the steering is - heavy and quick and it takes some doing to keep from weaving down the track. But as I adjust to the car and pick up speed. the steering improves, getting lighter and precise. I go faster and realize that the car sticks to the pavement, partially because of its ground-effect design, which is just beginning to work, but mostly because of its suspension and those very wide Goodyear tires. On occasion, I hesitate going into a turn and the car feels loose. But a blast of power plants its tires firmly on the roadway and sends the car scurrying off to the next turn. At times like this I'm aware of the engine's excellent mid-range torque and its flexibility. And its noise, which reaches 115 dBA at redline. With each lap I gain confidence in the Jag's handling and although I do not reach the car's-nor my-potential, I'm convinced that I could do so. Perhaps some other time when I've been fitted to the car and when the Camel GT championship is not at stake.

Chapter Six: It is midway through the 1983 IMSA season and the Jaguar has finally hit its stride. Although. Daytona is another disaster-a suspension part breaks and sends. the car into the guardrail-and Miami and Sebring are nothing to shout about, it all comes together at Road Atlanta where the Jag wins. At Riverside, Adam hits a patch of oily roadway and crashes. But at Laguna Seca and Charlotte, the XJR-5 is 2nd and 3rd respectively. By Lime Rock, it's back on top with another Camel GT victory. End of story, but certainly not the conclusion of the Jaguar XJR-5's adventures and the team's quest for the Camel GT championship. If Bob Tullius, Bill Adam and Group 44 succeed, 1983 could go down as the year of the cat in IMSA annals.

Author: ArchitectPage

Road Atlanta