CAR MAKERS FROM THE 60ies

Carol Shelby USA

Cobra

Racing has to be directed from the top. When you got a bunch of yucks down in the mill bucking for each other's jobs, the whole thing gets pulled apart and you can't do anything," Carroll Shelby said, hanging one long Texan leg over the corner of his desk. The pungency of expression is typical; the kind of astute business judgement that is behind it seems somewhat incongruous coming from Shelby, who has seemed to take such great, gleeful delight out of playing the nonbusinessman in the past. "I don't think for a minute that I got enough. sense to run this operation all by myself. Hell, I got all the problems that Ford Motor Company has, on a minor scale-product development, research, supplier contracts, dealer organization, warranty, and 'all that sort of thing-without the resources available to help me solve them. All I can do is try to find the people who can solve the problems. And then I can run the fun part of it.

"I'll be frank - I was thinking for a while about getting out of the automobile business. The problems didn't seem to be worth it. But I began running across some good people, putting together a tight organization that can handle the business, and the whole idea began to get exciting again. If I've done anything worthwhile, it's only been to bring things--and people-together. Like the V -8 engine and the AC chassis."

If there is any doubt about the astuteness of the business judgement, a glance at the success of the Cobra will dispel most questions. If it's necessary, a few more items on the profit side of the ledger might be toted up:

Carroll Shelby was the first American to make A Good Thing out of road racing. He parlayed a natural skill with a racing car into a spectacular career of a stature that only Dan Gurney has since approached.

After nearly everyone else involved in American road-racing had battered away at the doors around Detroit and Akron until their knuckles bled, and had come away shaking their heads, Shelby came away from those cities with firm and mutually advantageous business commitments-with the first two American firms to get serious' about road racing. Goodyear and Ford.

While other manufacturers interested in racing have produced cars, and then thought up, piece-by-piece, accessories that might help them go racing, Shelby homologated with the FIA everything he could lay his hands on or imagine in the dark of night that might someday bolt onto a Cobra automobile. As a result he's been able to field a race ready car in the GT class from the beginning, and never mind the complaints about those things being nearly modified cars. If there's anything that characterizes a racing Cobra, it isn't modification-it's foresight. Or, as Shelby puts it, "Right now the secret of success in road racing is to come up with something that you can build a hundred of-cheaply. And that's where Ferrari is going to foul up." This prediction was made about three weeks before the recent 12-Hour at Sebring, at which race it was borne out. In fact, a year ago at Sebring, C/D quoted Shelby as saying, "Next year, Ferrari's ass is mine." Exactly a year later, Ferrari GTs lost Sebring, and then Le Mans, for what seemed like at least the first time since the dim red dawn of time.

But the real secret of the Cobra is predicated on another sort of judgement entirely, peculiarly astute and peculiarly revealing about the progenitor. "In England, in 1954 when I was with Aston Martin, I was saying that the United States would have drivers just as good as anybody else's by 1960. And I said that by 1967, the important ideas in racing would be coming from this country. I still think it is true."

In this sense, Cobra fortunes are built on the fact that we are now reaching a golden age in road racing, akin in meaning (if not in regulations) to those startling years of the late Thirties. The people who began getting interested, as kids, in 1950 who began subscribing to Autocar and attending sports car races; the legendary TC owners-have now gotten themselves formally educated, have entered professions, often guided or swayed by this interest in automobiles, and are beginning to have some income.

These are the people who are now ready to buy cars, but who want sophisticated chassis, tasteful styling, technical modernity. They are responsible as a market for a tremendous upgrading of the domestic product. We are all reaping the technical harvest sowed in the early Fifties. Often times these people have gone directly into the automobile business themselves-and after spending 10 years absorbing, technically, what's going on with cars, they are now ready to apply that technical background.

From these ranks are coming an increasingly skillful, increasingly large stream of mechanics, drivers, engineers,. fabricators, organizers: managers, and-it is to be hoped eventually, as it already has occurred in the case of Shelby-constructors. These are the people that Shelby is finding. Southern California happens to abound with them. These are the people who have made the Cobra such a success so quickly, and who are most apt to keep the car and the concept advancing.

Because let us not kid ourselves. Denigrate all you want, about an archajc chassis and a bastardized engine swap, about hot rod sports cars and a lack of engineering so phistication. But don't look at any records while you are spouting off in these directions, or you'll tend to trail off into silence. There's an old adage about first being first and second being no place. And the Cobra is unquestionably the fastest production car in the world today. It will unquestionably manhandle any other car in its racing class. It has left a trail of broken course records and captured championships all over the North American continent.

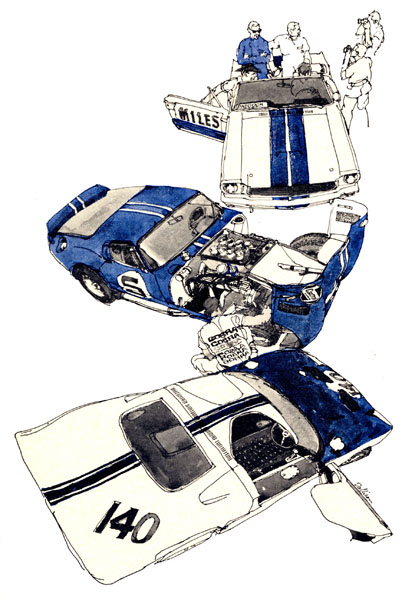

Where does it come from? The quotes at the beginning of this article come from a weekend I spent in Venice, California, poking around the Cobra works, snooping in parts bins, sprawling in Shelby's office, and eavesdropping on conversations. I sat in on a session that was an object lesson in the Shelby Philosophy of Business Management; Carroll got together a couple of consulting engineers from Aeroneutronics (a far out advanced theory space technology firm that had indirectly advised Pete Brock on the aerodynamics of the new coupe before it ran at Daytona), his chief technical man Phil Remington, Ken Miles, and a couple of other people. The group happened into his office inadvertently for coffee, and began discussing what direction a carthree or four years in the future that could be built by a firm the size of Shelby's-might take. Before long, everyone was sitting on the floor with his shoes off, sketch pad in hand and pencil flying, arguments raging about waffling and plastics and structural rigidity. Carroll paced in the background, adding very little except an occasional question that he tried to make sound dumb but never was less than incisive. It was a fascinating couple of hours.

The place was somewhat busy, anyway. It was Saturday morning. Carroll was leaving on Monday for New York, where he would speak to the Madison Avenue Chowder Society and the SAE, and he had speeches to write. As soon as he got back from New York, he was involved in a trip to Japan on a consultant basis, and would continue around the world to get to Le Mans hopefully in time for the test weekend. Meanwhile the Sebring cars were being prepared, and a few interesting problems were cropping up in stuffing the 427 cubic-inch Ford engine into one of them for the prototype category. Plans were beginning to jell to bring the coupe back from Sebring via San Angelo, Texas, where Shelby planned to put the car on the Goodyear test track and try to break Foyt's recent 2004

mph record lap (wouldn't that frost 01' A.J. if I broke his record with a sporty car?" You get the impression that Shelby likes very much to bug Texans). Meanwhile, four coupes were to be built for Le Mans, one of them to have the 427 in it. There wasn't much time for that. Two King Cobras (Cooper-Fairlanes) had just been built and delivered to the Comstock racing team in Canada. And Briggs Cunningham had ordered a coupe for Le Mans.

Of course it was planned to campaign the cars on the USRRC circuit, and that involved a lot of car shipping and planning. Meanwhile, production of the street machines continued apace, the mail order business threatened to inundate every square ipch of office space for miles around (decals, T-shirts, etc., plus Cobra goodies as bolt-on accessories for frustrated Fairlane owners). And the Goodyear tire business, which is so successful that it has been in trouble for housing space from the beginning, no matter how fast Shelby rents new warehouses, was due to be moved out to Riverside fairly soon.

USA

Car Designer/builder - Cobra

Carol ShelbyIn fact, moves are planned for everything-the strongest single impression you get (after you stand

transfixed gazing at the tiers upon rows upon stacks of Ford Fairlane engines) is of a yeasty, growing, fast-developing business with infinite possibilities and infinite energies. There is distant talk about new offices and new factories and new facilities going on all the time and those good people that Shelby keeps talking about are planning the best use of the new possibilities.

Meanwhile, Carroll Shelby swirls through it all, whipping up eddies in his wake. He'd just had the knee operation (to repair an old racing injury) that was eventually to put him temporarily into a wheel chair at Sebring. He wasn't limping while I was there; rather, he was moving well and keeping up' a wandering pace. Shelby doesn't hurry, ostensibly he tends to dawdle and poke into things as he goes. But he has a flat and penetrating voice, and he tends to talk at substantial volume, perhaps a habit from years of trying to make himself heard over racing engines. He also makes grand gestures, keeps an electric cattle prod handy in the office for an occasional gag, and tends to lapse into language that is more pungent than even the liberal editorial policy of C/D will allow.

I got the Cook's Tour: two buildings, one devoted to the production line for street machines, storage of engines, undelivered cars, design work, the school vehicles, the tire business, fine finish work and show cars; the other all racing division

and dyno room and more engines, parts bins and secretaries, racing cars going together, executive offices. Formally I think one of them is Shelby-American, and the other Carroll Shelby Enterprises, Inc. The distinction was explained to me, but I've forgotten what it was. The buildings, or at least one of them, used to be the home of Reventlow Automobiles, Inc. (i.e. Scarab).

Shelby's office is dominated by a low table covered with Cobra trophies, plus mementos of Carroll's racing career. When I was there, right after Augusta, the Cobra crew had just presented him with a 6-foot smudge pot from a Georgia fruit orchard; they'd gotten cold while working on a car in the middle of the night, borrowed the smudge from a nearby field, and had brought it back to paint it up as a trophy and present it to Carroll. On his desk was an outrageous porcelain figurine of four guttersnipes playing poker.

It was colored in virulent reds and yellows, and must've measured a foot and a half in diameter and eight inches high. Shelby had passed it off to the office staff as "some of that extremely valuable collector's porcelain from Italy that I've started to invest in," and was having great fun watching the goggle-eyed and headshaking reception that the calmer heads on the staff were according it. It was awful, but he was admitting it to no one. It was interesting to me that though there was memorabilia of his racing career about the office, there was no cloying collection of trivia. There were as many trophies around with the names of Miles and MacDonald engraved on them as there were from Shelby's career.

It was a njce time to be at Shelby's; the staff was feeling tough and ready, and some fascinating projects were in the wind. Plans were then to get a Lotus 30, the equivalent Cooper sports racing car, and the nearest equivalent Genie, and turn them all over to Aeroneutronics for analysis. From this Shelby-Amerjcan could then plan a proper racing car. I don't know if the project is underway or not. Carroll had just settled the Sunbeam-Fairlane conversion; after doing the development work, he was not getting involved in the manufacture, but taking a royalty on the cars that were sold.

Technical director Phil Remington had just returned from England, where he'd been helping with the Ford GT. Remington was one of the Reventlow employees, and is, according to Shelby, about as astute and cool a head as there is in the business these days. Now he was home to begin preparing the Shelby Le Mans effort, and the possibility of a head on Cobra/Ford GT clash was a distinct possibility for the near future. It'd taken some time for this to dawn on Ford Motor Co., but it finally had, and their first reaction was to ask Shelby to withdraw from the race. Thanks very much, but no thanks. A little reason prevailed-Ford was going with one, maybe two cars,' according to plans at the time, Shelby with four. Finally it was all solved. In the unlikely event that after 23 hours, things had resolved themselves to the point that there were only Cobras and Ford GTs in contention, then negotiations would have been reopened. Until then, they'd just go ahead and compete with each other. After a few days watching the Shelby operation, if Benson Ford and Carroll Shelby had stepped back behind the pits at Le Mans to negotiate during the closing stages of the race, I'd have put my money on the Cobra. I know a winner when I see one.

More Le Mans Cars from the 60ies onwards

Author: ArchitectPage

Between these two feats of skill, Shelby's efforts abroad have been plagued by naive planning, hastily prepared cars and an overload of work. And Ferrari was always ready to pounce if Shelby's men made a mistake.

After a fairly successful Le Mans trial session in April, the team arrived in Sicily with a batch of brand new cars for the Targa Florio. Some critics charged the Shelby operation with overconfidence, others said the Cobras were basically unsuitable for racing on rough circuits.

In any case, Gurney put a Cobra in second place on the first 44-mile lap. A Porsche was running first and it's tempting to get cocky about blowing off one of those funny little German cars. But the mercilessly tough roads were hammering away at the suspension, the steering and the gearbox of all five Cobras entered, and they slipped from contention. Gurney nursed his bruised Cobra to a blistered eighth place.

The 500-kilometer race at Spa was better. It was no small consolation when Phil Hill, driving the Cobra coupe, set the fastest lap and a new GT record of over 129 mph. But it didn't save the day; he had already spent an eternity in the pits during the opening laps of the race attending to a clogged fuel filter. His subsequent burst of speed was only a Moss-like demonstration of coming up from behind when the odds were hopelessly against him. The first Cobra home was Bondurant's roadster, in ninth place and a lap behind the winner, a Ferrari GTO driven by Mike Parkes.

At the Nurburgring, the coupe's streamlining would have been useless; it wasn't even entered. The mechanics looked exhausted and the cars looked worse. The team showed up early for practice but it was obvious that the cars weren't right for the course. Shelby should have known better; he'd been there as a member of the impeccably-organized Aston Martin team and he knew what it takes to score on the 'Ring.

A British team had entered two Cobras, Shelby was down to two team cars and another was fielded as a private entry. The private Cobra recorded the fastest GT time, but it was more than 30 seconds slower than the fastest Ferrari prototype and was later eliminated in a race accident. Two Cobras had already been wrecked in practice, one still hadn't been repaired after a shunt in the Targa, and the other two were short on reliability and long on niggling troubles. After a tragicomic seven hours one finished 23rd and the other-47th in a finishing field of 51. A Ferrari GTO finished second.

A week before Le Mans, Jo Schlesser shattered the Ferrari opposition in the GT class at the Mount Ventoux hillclimb, but few people took any notice. Then came the 24-hour and the repeat of the Sebring finish.

Carroll Shelby invaded Europe with the intention of snatching the World GT Championship away from ever-potent Ferrari. He ran in to some pretty tough sledding at the Targa Florio and the Nurburgring, but proved once again that a Cobra can cream Ferrari GTs on any smooth circuit-even after 24 hours.

The battle for the GT Championship is far from over (as of this writing), with two hillclimbs and the Tourist Trophy still to be run in Europe. The penultimate race will be at Bridgehampton, N.Y. on September 19-20, and should victory still hang in the balance, the tie-breaker will be at the 1000-kms. of Paris.

In 1965, unless Ferrari can work some miracle, the GT championship won't be the cliff-hanger it's been this year.