There is real competition in the 1967 Can-AmFord vs. Chevrolet, Goodyear vs. Firestone, the U.S. vs. the WorId . . . you need jacks or better to open in this game.

The Canadian-American Challenge was designed with the reasonably ambitious goal of becoming the greatest road racing series in the world. It would bring the top drivers and cars to the North American continent, to run a half dozen or so races under an American formula-big, stockblock engines in fairly sophisticated two seater sports/racing car chassis-and establish road racing as a major league sport for once and for all.

To do that the Can-Am needed big bucks-and it got them. In its second year, 500,000 of them on the surface and perhaps several millions where no one could see them, in tire company, accessory company and manufacturer's contracts. It also needed real competition: Ford vs. Chevrolet, Goodyear vs. Firestone, the United States vs. the world-and, as the 1967 series opened in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, it looked as though, that, too, was forthcoming.

All this was going to make road racing the spectator sport that it had never been before, because without the oval tracks' yellow flag (which makes a new race of any competition five and six times during an event-every time there's a spin or an accident), the only substitution was genuine competition; jacks or better to open.

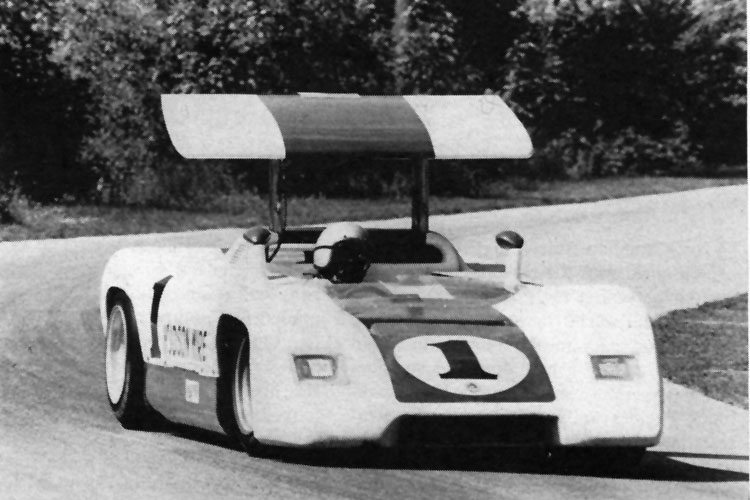

That's what it looked like at Elkhart Lake's Road America circuit on Thursday, August 30, before practice. By the evening of September 3, after the first CanAm had been run, the series was threatened with disaster. Denny Hulme in a Goodyear-shod McLaren-Chevy M6A won it wire-to-wire, and the only real competition came from a second McLaren M6A, the other team car driven by builder/designer and team leader, Bruce McLaren.

Second' man home in the '68. Can-Am opener was USRRC Champion Mark Donohue in a new Lola-Chevy Mk. IIIB; third was another Lola IIIB driven by '66 CanAm champion, John Surtees.

The Ford effort, which, in fairness, got started very late, did a lot of staying at home. Only John Holman's (half of the Holman-Moody racing shops) imprudence prompted him to bring a 15-seconds-too slow Honker II-and even Holman (who bills himself as Honker L a left over from his truck-driving past) had the sense to trailer his car home before the race.

The Honker probably wasn't going to be ready until the third race in the series Mosport, September 23, and in any case didn't look likely to scare anyone but it's verv brave driver Mario Andretti.

Shelby's cars (only one, probably) stayed home like the rest of the Ford factory and quasi-factory entries because, like them. they suffered from a lack of sorting out, again, no time. There went the subway series of Ford vs. Chevrolet.

Donohue, whose all American looks and manner challenge Dan Gurney's, kept the isolationist hopes alive, and so, in a way, did Jim Hall, whose 427 cu. in. Chaparral 2G, topped the horsepower race, but who could do no better than fourth. "I guess I better give up team managing and do a little more driving," said an aching Hall after the 200-mile race. Chaparral boosters weren't too worried. Hall, who had spent the season guiding his long distance cars in European endurance races, was rusty as a driver-but sure to regain his driving form. Dan Gurney, on the other hand, was a real contender, and his 378 cu. in. Gurney-Weslake V-8 was the only Ford to work at all well. While he was in there he was as quick as the McLarens, but his throttle stuck, he spun and flat-spotted his tires. He eventually quit with gear shifter problems.

The Ford G7-A didn't even show, the engine wasn't working, and the Ford types thought they would probably go to something less exotic than the three-valve 429 for the West Coast.

Before Elkhart and after Elkhart, the contenders seemed the same: McLaren's two cars, the Penske Lola-Chevy team (Donohue and George Follmer, substituting for Chris Amon, who was tentatively scheduled to drive a Ferrari Group 7 car entered by Bill Harrah), Surtees (Lola) and Hall (Chaparral). All Chevrolet engined, all extensively tested. Gurney was an outsider from the start, never to be counted out. always the great crowd favorite, but suffering from an inclination to

go off in too many different directions in stead of down one road very fast and with great determination and preparation.

And that is what's required to win the Can-Am-which still might prove to be what it was originally intended-the greatest road racing series in the world.

Including the 200-mile Elkhart Lake opener, there's 1209 miles of racing in the Can-Am: 250 miles of Bridgehampton, September 17; the Player's 200 (actually the Player's 197) at Mosport, September 23; to the West Coast for Monterey Laguna Seca's 202-miler, October 15; down the coast to Riverside and the 200 mile race there, October 29; and the Stardust for the November 12 finale of 210 miles. Riverside offers the top prize money-$40,000-but they're all close: Elkhart, $39,000; Bridgehampton, $25,000; Mosport, $35,000; Laguna, $35,000; and Stardust, $35,000 plus all you can win at the Las Vegas tables. The point fund is additional, a device to make. up for the lack of appearance money (which only- one track pays), and this year it's $90,000, with the series winner getting $31,500, the second man $17,000 and paying down to the 10th man with $2,700.

A total of about $500,000 over 1200

miles with about 60 cars competing. If one driver in one car won every race possible and qualified fastest in each, he'd take home $54,200 in prize money, $31,500 in series fund money, and about $15,000 in contingency money-over $100,000. A reasonable budget for a two-car Can-Am team is about $150,000. What makes it all possible if you have to spend more than you can possibly win? The contracts, that's what. And that's what makes it tough on the independents.

Supposedly, one tire distributor, who also races, was dickering for $250,000 from his parent company for a 2 car team,

and support for one well-known independent (one car) was pegged at $100,000.

But this is the wildest kind of speculation on the covert money supply in the CanAm. A closer estimate comes from a team which proposed to field two cars, one with a GP name driver, the other with a name driver without GP experience. The $150,000 figure was taken as projected costs: $75,000 was asked from a tire company sponsor, $25,000 from an auxiliary sponsor, several thousands from smaller sponsors. Given the earlier prize money figures, as well as the appearance money schedule at the one track which pays the name starters (somewhere on the order of $8,000 $6,000-$4,000-$2,500-$1,500 for the top six teams), and the team expected to have about $75,000 in the bank before racing started. Two cars cost $40,000. Engines (Traco Chevys) about $5,000 apiece and travel expenses nearly $1,000 a race. Additionally, the four mechanics were to be paid $200 a week. So the team was into the Can-Am very close to budget if nothing

went wrong. In order to break even it would have had to win a couple of races, take some seconds and thirds and at least third overall in the series standings. When the tire sponsor offered only half of its projected contribution, the team pulled out.

Another team, which stayed in the CanAm, and has a very good chance of winning it, also is fielding two cars, but has an oil company as a primary sponsor. Added to the tire company it represents, the oil company money very probably got the whole effort off the nut before a wheel turned.

Thus, the covert money is what makes the Can-Am go despite the hue and the cry of the $500,000 series. It's more like a $2 million series, if all the figures were known-and publishable.

Will it continue, this underground river of dollars? And is it good for the future of the Can-Am?

If manufacturer entries are classified as "covert money," and if the Ford projects get off the ground-which they still might-the answer is an unqualified "yes." Ford brings A. J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, Jerry Titus and Parnelli Jones to the series with a real chance of winning. Ford money does the same for Dan Gurney, although not to the extent that the company would have you believe. Chevrolet may well be supplying super-secret covert money to Jim Hall and Roger Penske, even if it takes the form of inventory (parts and car) credit for their Chevrolet dealerships. Akron's cross-town war between Goodyear and Firestone has made Indianapolis a brilliant, international race.

If it reaches the degree of escalation in the Can-Am it has achieved in USAC's Championship Trail. the prize money in the Can Am will be almost incidental.

So, if the money continues-and it will, for a while at least-the viability of the Can-Am will depend in a large degree on the continued availability of drivers and, perhaps more importantly, crew chiefs.

Only one of last year's top 10 finishers is out of the Can-Am this year. Phil Hill and Jim Hall have parted company, and, at any rate, Hall is fielding only one car. Amon, who drove for McLaren in '66, may be back with a Ferrari this year but don't break open your piggy bank and bet on it. So the Can-Am drivers are back, and with them are more USAC pilots, including Roger McCluskey in the Pacesetter Homes Lola. Foyt, Andretti and Jones should be mounted in more competitive machinery always, if Ford gets off the ground-and Frank Matich has come up from Australia to join the chase. On balance about half of the world's top road racing drivers are in the series: but the exceptions are significant, and include Jim Clark, Jack Brabham, Graham Hill (and Phil Hill), Jochen Rindt, Pedro Rodriguez and Lloyd Ruby. Where are the new drivers to come from? A list of qualifiers at Elkhart includes the names of some staggering unknowns Ronald Courtney, Fred Pipin, Ross Greenville, Gary Wilson and the ever-popular Marshall Doran. Perhaps tomorrow's John Surtees or Jim Hall is among them. If not, they must come from the USRRC lot, or the present Formula Two and Three drivers in Europe.

Nor does the USRRC seem to provide much in the way of future greats for the Can-Am. Mark Donohue made this year's series look like a cross-country, whistlestop Clay-Patterson rematch series. He won wherever he went, with one exception, and with the best six races counting for the points crown, came up with a perfect record. But Donohue is an established star he's a product of a year ago's USRRC and Can-Am. Where is this year's Donohue? It may be a young man from Sharon, Connecticut, Sam Posey. Posey showed great promise in the USRRC this year and has been coming along well. But he has chosen to build a car of his own-in partnership with Ray Caldwell, who designed and built the Autodynamics Formula Vee-and Posey isn't going to win in a league as tough as the Can-Am with a brand-new car. Moreover, he knows it. All he wants to do is get the car running well by the middle of the series. His effort is said to be costing him about half a million dollars. It's not likely he'll win much of that back in '67, but Posey is driver enough, and Caldwell designer enough,. that the combination might be very tough a year from now.

Peter Revson is a driver of unquestioned ability, but he's on a second-rate team. Dana Chevrolet tried to win the USRRC with a massive expenditure, and a team of Revson and Bob Bondurant in a pair of McLaren-Chevys. Bondurant crashed and was replaced by Lothar Motschenbacher (who also crashed). The cars didn't work well at all and they were overwhelmed by the Lolas. So Dana has gone out and bought a pair of Lolas. They have Revson and they have Motschenbacher, either of whom might be the next top flight American of the Gurney caliber, but the USRRC effort was beset with changes of mind and reported internal dispute. That sort of thing doesn't win races-let alone the Can-Am.

Brett Lunger, Don Morin and Skip Barber are bright young drivers, all coming along, all capable of putting one good race together-and when they do, of finishing

third. But all three are at least two years away. Bill Eve and Mike Goth, who looked very promising last year, were disappointing in the spring pro shakedown.

It is no good looking to USAC or NASCAR for new talent in the Can-Am; they're having a rough enough time providing for their own races. The only possibilities are Al Unser in USAC and maybe, just maybe, Donnie Allison or James Hylton from NASCAR.

Still, they're more drivers looking for cars than the other way around, and the reason for that is the lack of crew chiefs.

Crew chiefs and team managers. Once you've said McLaren, Surtees, Penske, Gurney and Hall the list about stops. Caldwell is as good as they come, but the Autodynamics team has car-sorting problems.

Phil Remington and AI Dowd are also major leaguers, but Caldwell's problems look like a taffy-pull compared to what Shelby has on its hands. If you could get a car set up right you could get Brabham, or Ruby in a minute-maybe even Jim Clark. Trouble is, you can't get one set up right-and right now, that's the real bottleneck.

That, and this business with the Ford Motor Company. FoMoCo had a raft of racing types in the pits at the Can-Am opener, cheering Dan Gurney. And all the while in Detroit and Los Angeles and Charlotte, there were the real Ford team cars in various states of disarray. The great hope of the series, the thing that was going to put it on the map for once and for all the gutsy battle between Ford and Chevrolet on the race track-fizzled out by the light of someone's midnight oil. That didn't keep the season's opener from being a beautiful race, and it didn't keep the track owner and promoter, Cliff Tufte, from counting his biggest house ever - 53,100. But if Ford could only, somehow, some way, get going before it was too late, there would be no end in sight to how big the Can-Am could get.

It is already remarkable that the series exists at all-born as it was from the Sports Car Club of America, an-essentially amateur organization - gone- partially- professonal- but-unable- to-q u i te-make- up- its mind-to-go-all-the-way. Ten years ago most of the tracks on which the Can-Am are run were artichoke patches or prairie-dog runs. Ten years ago, the promoters who are making things work were bank clerks or pro-football players.And there is nothing to say that the Can Am can't get bigger-so that it goes quite beyond North America preaching the gospel of a uniquely American formula. There is talk of expanding it in 1968 to include a race in Germany, a race in England, two in Japan, and perhaps two in Australia.

But it all seems to turn on whether the Can-Am is going to become a success at the box office. And that seems to turn on whether Ford Motor Company gets going before the season is over. A sweep of the West Coast races would do it just fine. A very convincing win of two races could even do it. But the West Coast tour in 1967 looks as though it's going to be make-or break for the Can-Am as a major league enterprise.

The whole thing was said in a curious little interchange in the pits at Elkhart between John Holman and Jim Hall. Holman's new car had just been brought in by Mario Andretti after turning a lap that was 15 seconds or more off the pace. Jim Hall was working on his car, puzzled that he was five seconds quicker than the previous track record. . . and seven seconds slower than the McLarens.

"Say, Jim, what do you think of my new Honker?" asked an oddly proud Holman - Hall looked up, paused a moment, and answered, "It's perfect."

other fifties races:

other sixties races:

Author: ArchitectPage