Money wasn't one of the major problems faced by Amon when he decided to try his hand at motor racing. He came from a rich farming family with properties at Bulls near Wanganui in New Zealand and consequently had more financial lifts up the ladder than most young drivers can expect. But money can't help you once you slide into the cockpit of a racing car-when the flag drops, Daddy's help suddenly stops and your progress from there on is very much a matter of personal skill.

Amon had followed European motor racing from magazines at school and as soon as he left he bought a converted dirt-track midget. At 16.5 he was facing the starter on the short Levin circuit not far from his home. It was a handicap event and he led for six laps before the engine blew. He ran the midget in a few hillclimbs but it was a far from competitive machine and he sold this to buy a Cooper, one of the first Formula 2 single-seaters with a single-cam 1500 Coventry-Climax engine. He raced this once at Levin to take a second spot but it wasn't fast enough to suit the youngster and he traded it on a 250F Maserati. This-was the car that BRM had used as a test vehicle before building its front engine 2.5 liter cars and had disc wheels and disc brakes.

The sight of a boy in a sports shirt wrestling with the Maserati was a stirring sight and those who fancied themselves as talent spotters remembered that he handled the big car in a very polished fashion.

AFTER A couple of seasons learning the ropes of racing with a then-fast car, the Maserati was sold to buy a 2.5-liter Cooper and Australian team boss David McKay took the young New Zealander under his wing for a few races in Australia. It was obvious that he had the talent to be a very good driver but being a star while still a teenager didn't suit McKay's sense of the proprieties. So Amon bought a slightly battered later model Cooper from McKay and took it back to New Zealand to rebuild it and try his hand at big-time racing on his own.

This was a disaster but it was this move that brought him to the attention of Reg Parnell who was impressed despite the appalling lack of organization and luck during the 1963 "Down Under" series. Amon had run himself into debt with his parents and being determined to prove himself a solo success and at the same time run the operation on a shoestring, he had more than his share of worries. He was fortunate that his parents realized the real efforts their son was making to be a racing driver and supported him through that season as drama dropped him from race after race.

Reg Parnell was looking for driver potential and he was probably well aware that Amon could drive well even if his car didn't have the staying power. He was good material and Reg invited him to Europe for a season.

As the 1963 season opened in England, Amon found himself on a grid full of stars that he had only read about in magazines. At first he was treated with a fair amount of what could have been called reserve but which was often resentment from English drivers with more experience who were not being offered the same opportunities that Parnell was putting before this 19-year-old Kiwi.

Private teams never seem to have the razor-sharp-power and performance of the works cars but while his Lola was a runner Amon showed that he was able to mix it with the "boys" on the championship circuits. The biggest change he found was the strong professionalism of the "sport" in England. Racing in New Zealand had been a hobby: No one there expected to earn a living from it but in England he suddenly found himself eating, drinking and sleeping motor racing with that consciousness of a top performer in any sphere who knows he has to be that much smarter in each performance to stay ahead of the herd.

HALFWAY THROUGH that first season Parnell told Amon and teammate Mike Hailwood that if they made a go of it through the '63 season they were "Really going to have a try in '64." (Parnell was certain, by the. way, that Hailwood had a Surtees-like 4-wheel future if he was coached properly.) Parnell had arranged to buy three monocoque Lotus 25s from Colin Chapman and had organized three CoventryClimax V-8s done up to the latest factory specifications to give his young proteges a fair chance to prove their worth.

But early in 1964 this dream ended suddenly with the death of Reg Parnell. News of his death came as a terrific blow to Amon who was preparing to race a 2.5 Lola in the New Zealand Grand Prix the next day. Parnell had given him a motor racing opportunity that hadn't existed since the days of good fairies and magic wands, and as well as losing a father-like "friend, he didn't know how he fared for a drive in Europe. The rest of the New Zealand season was a trail of chaos with the Lola that resulted as much from Amon's preoccupation about his future as it did from the general orneriness of the motorcar.

Tim Parnell Reg's son, took over the team. Tim had raced his own cars for several seasons and knew the ropes but Tim was an honest plodder where his father had been a flyer. Reg had the foresight and the promoting ability to forge ahead but his son could not match his bubbling leadership.

They couldn't afford the Climax V-8s and took customer BRM V-8s in their place which were down on power, and necessarily tight purse strings resulted in such economies as 5-speed gearboxes when 6-speed units were needed. The cars were plainly uncompetitive and both Hailwood and Amon had a low season. It was enough to kill Hailwood's enthusiasm for the 4-wheel-world and he went back to motorcycles while Amon was in danger of being cast up on the pile of racing drivers who might be stars if only given the chance.

His one high spot that year was when Tommy Atkins put him in his Cobra for the Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch and in a hairy wheel-to-wheel dice that lasted throughout the race Amon and Jack Sears had the excited crowd on tip toes as the Cobras thundered around the tight track inches apart. Amon finished a fraction behind "Gentleman Jack" with bleeding hands but the satisfaction that he hadn't lost his touch and that big cars were definitely more satisfying to conduct than the smaller high-revving 1.5 liter FI V-8s.

A MON'S HOPES for '65 were very bleak until McLaren offered him a ride in a 2-liter sports car and a position as a test driver in his growing team. It wasn't the sort of opportunity that an established GP driver would be expected to jump at as it meant severing the GP link which, as a lot of drivers know to their loss, takes a lot of re-forging.

However, Amon was aware that since Parnell died there had been no one to learn from ("I think Mike knew even less about than I did - which wasn't much) McLaren was a patient teacher who laid down rules. For the first time in his career he was benefitting from discipline.

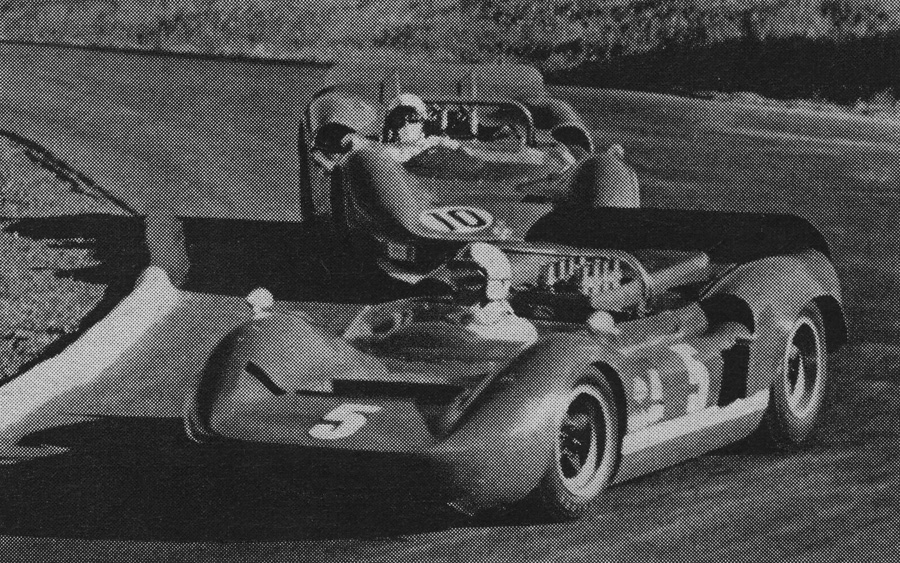

As well as some abortive outings in the 2-liter Elva-BMW wished on the team by their production link through the McLaren-Elva sports racers, Amon covered hundreds of miles testing for Firestone, first in the McLaren-Elva and later in the single-seater prototype Formula I car. He deputized for McLaren in the Martini Trophy at Silverstone after a fuel line fire had burned Bruce's neck in practice and he drove the scorched car from the -back of the grid to a fine win. At St. Jovite in Canada he had another win, this time after a hectic race with Hap Sharp in one of the all-conquering automatic Chaparrals.

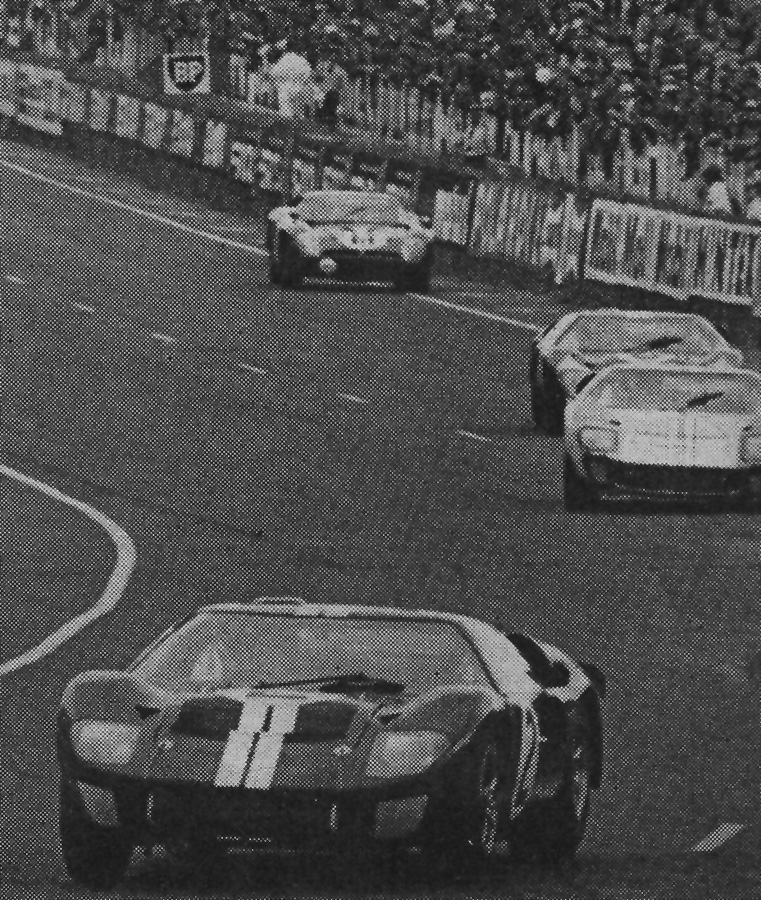

McLaren influence earned him a place in the Ford Le Mans challenge in 1965 and he was vastly impressed to be chosen by Phil Hill as his co-driver in one of the 7-liter GTs. While Phil was hovering above the Sarthe circuit in a helicopter giving a TV commentary, his young teammate had blasted off into the lead hotly pursued by fellow countryman McLaren in the other 7 -liter.

McLaren then led, and the pair dominated the race, giving Frenchmen a far more impressive concept of New Zealand than conveyed by the Kiwi on the shoe polish tins. But all the Fords dropped out, Amon's with transmission trouble.

FOR 1966 he was looking forward to a ride as second driver in the McLaren Grand Prix team, but though there were two immaculately finished and technically advanced cars ready to race, engine troubles plagued the team. Development troubles with the 3-liter version of the 4-cam Indianapolis Ford V-8 meant both cars were non-starters in most of the championship races and although McLaren tried an Italian Serenissima V-8 it was plainly uncompetitive and did not show the true form of either car or driver.

Once again Amon's high-spots came with the "Big Bangers." He had another win in Canada with a McLaren Elva, and at Le Mans the Ford GT he shared with McLaren won the race.

He wasn't driving at the disputed finish, of that race, however, as has been reported., He was being interviewed on television. During the fall season, driving the team's second McLaren-Elva Chevrolet, he set the fastest lap at St. Jovite while coming far behind to finish third, then took second behind Gurney at Bridgehampton.

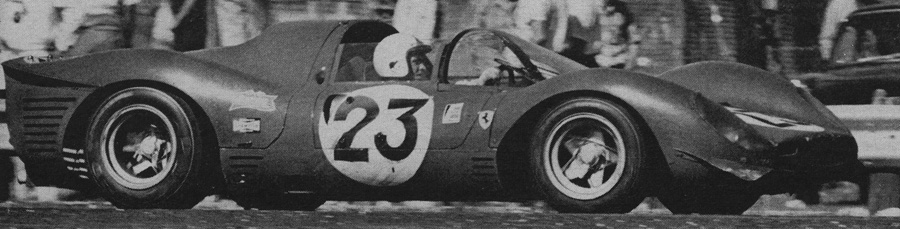

For 1967 he has signed with Sefac Ferrari and is expected to be one of the regular drivers of Grand Prix cars as well asccampaign a prototype in the classic sports car races. In his first outing for Ferrari he teamed with Lorenzo Bandini to lead Ferrari's 1-2-3 sweep at the Daytona 24-hr race.

Having been around for five years on the- European scene, it is easy to forget that Amon is still the baby on the grids at 23. He says until now being the baby of the bunch has given him something of an inferiority complex, but now he is getting over it.

I used to hold the top drivers up on a sort of mental pedestal and always regarded them as being somehow superhuman. I was racing against them to be fifth or sixth at best and I lost a certain amount of the will to win. But now I've got a lot of that back. It's taken me five years to realize that the top drivers are human after all and that they're not unbeatable."

Recently married to Barbara Ann McLain, a young actress from Florida whom he met at Nassau in 1965, his social life is somewhat less demanding and he has showed a distinctly faster form on the track because of it. He smokes too much but drinks only enough to be sociable. In his bachelor years he rented an enormous house on opulent grounds in Surbiton but in 1967 Mr. and Mrs. Amon will be living in Rome.

He is a rapid young gentleman who has been across the threshold of stardom twice, briefly, and is working hard for his permanent pass.

Author: ArchitectPage