Formula 1 - 1964

Ronnie Bucknum

USA

about him in sixties

Post 1945 DriversAS RECENTLY AS july of this year, if anyone had suggested that the World Championship for 1965 could 'be won by a driver named Bucknum in a car named Honda, the proper prescription might have called for lots of rest and constant supervision.

Even now it isn't the sort of thing one likes to say in public. In spite of Honda's success in motorcycle racing - and Bucknum's in U.S. club racing, the fact remains that neither has had the slightest Grand Prix experience prior to this year. Yet, having been present at Honda's first, two Formula 1 appearances, Nurburg Ring in 'August and Monza in September, I cannot help thinking Honda could win in '65 with Bucknum at the wheel.

Watching Honda at work is an experience. It is a large team by GP standards, with nine men including the driver, and most of them actually work on the car. Yet the Honda garage is a quiet place, there is little conversation and a normal tone of voice is always audible. It's clear every man knows precisely what he's doing and how to do it, and is wasting no time discussing the matter. Moreover, when time comes for practice, or for the race itself, there is no last-minute scrambling, no mechanics trying to button down body panels an instant before the flag is dropped. The car is simply pushed out to the starting line and something in the manner in which this is done tells you that it's ready, or as ready as it was humanly possible to make it in the time allotted. The effect, in comparison with most equipes, is rather eerie.

Saturday afternoon, at Monza, I sat in the back of one of the Honda vans with Ron Bucknum and as he spoke it was easy to see that he found it all a bit incredible.

"You know, I was about ready to quit racing when this happened," he said. "I was 28 and didn't seem to be getting anywhere. If you don't make it by the time you're 27 or 28; you don't have much chance. I'd "begun to think maybe I didn't want to come over, here so badly after all."

He'd driven his first race in 1956 in a Porsche Speedster and at that time had had no idea of making it a career. A friend named Jerry Sheets had taken him to see his first event and he had become excited about it immediately. "I was single at the time," Bucknum recalls, "had enough money to buy a car, and it was just something that was fun to do.

"Of course I was lucky and won my first race, at Pomona, and I won pretty regularly after that."

He remembers being elated over those early victories. "I guess I got a little swell-headed around that time, at least all my friends tell me I did." And then: "Come to think of it, I did consider myself pretty damned good. That's some indication, isn't it?" ,

In spite of everything there had been a moment early on when he almost got out. He had met Nancy, a charming and attractive girl from his home town of La Canada, Calif. ("She baby-sat for my folks; I used to meet a lot of interesting girls that way, it's wonderful recruiting"), but Nancy turned out to be the one and, after they were married, "Money began to be a problem. I sold - the Speedster and decided to hang it up."

His retirement didn't last long. He got word that Lew Spencer, a top-flight California driver, was leaving Rene Pellandini. It was the opening he'd been looking for.

"Lew had worked selling cars for Rene and driving an AC Bristol for him in all the races. Well, Rene raced too, and I'd beaten him a lot of times so I 'figured he must have some respect for my ability. So I called him and told him I wanted to drive the AC and he said no."

Ron broke off to give a rather rueful laugh. "I don't think I'd realized before just how much I wanted to drive. I mean, I wanted that AC so bad it made me kind of sick inside.

"I said, 'Why'not?' and he said he already had a driver, and I said, 'Look, Rene, I've quit my job and I need work. I'll come down and sell cars for you.' Now, that was a lie, I hadn't quit my job-but the next day I did. Then I went down to Rene's and when he saw me he just threw up his hands. He'd told me he couldn't afford another salesman. I said, 'That's all right, I'm going to stay here and work for you whether you pay me or not.' Well, I knew about getting an advance against commissions for sales, and we finally agreed to that kind of arrangement. Naturally, when the next race rolled around I got to drive the AC because, after all, I was working for him."

Bucknum drove the Bristol for several months, scoring well against the newer and faster Porsche Carreras which were beginning to take over its class. Then he switched to an Austin Healey 3000 and later an MG-B, both for Hollywood Sport Cars.

"Of course, by then I'd made a transition, and the funny thing is I wasn't really aware of it. One night at a party Cal Club secretary Mary Hauser said something about; 'Oh well, now that you're aprofessional - I've forgotten just what but I suddenly realized she was right: Hollywood Sport Cars was paying my expenses, giving me about a hundred a race to drive for them, and I hadn't even owned a sports car for over a year. I guess it was about then I realized I was in racing for keeps, to make a' livirig at it if possible."

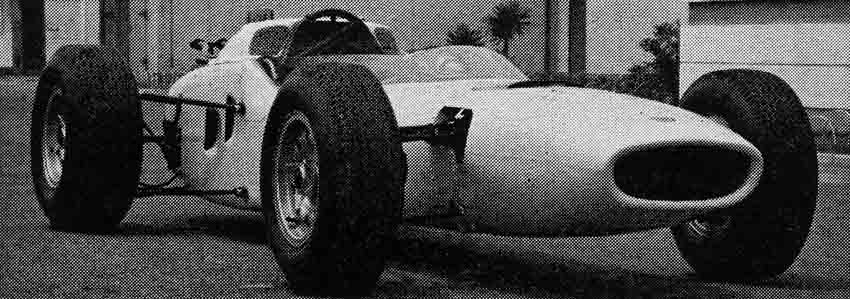

For a long time the possibiiity seemed slight. He continued to drive production cars and got a couple of rides in a modified machine, but the major' sponsors remained unaware or uninterested in him. In 1958 Donna Lynn Bucknum was born, three years later Steven came along, and by the beginning of the present year Nancy was pregnant again. The rising cost of family living was not being matched by Ron's race earnings, and there seemed nothing to do but go back to his former occupation, surveying for a private construction firm, and become another face in the crowd. Something had to happen. And it did.In March he was approached by a representative of Honda. Shortly he flew to Tokyo to climb behind the wheel of the first formula car he'd sat in in his life (and the second non-production machine he'd ever driven). "It was the most frightening experience I've ever had," he says, "and personally I thought I was pretty bad."

Honda did not think so. It signed him to a contract guaranteeing him four races in 1964, or the equivalent in payment, a contract which: "I think, makes me one of the best-paid drivers in the sport." In following months he flew four more times to Japan to complete tests on the car, then joined the team in Europe for the Grand Prix of Germany in early August. In his first Formula I effort, on the most difficult road circuit in the world, and in the rain, he outdistanced several well-known entrants and lasted 12.5 of the 15 laps before steering problems put him out. A month later at Monza he qualified in a tie for 9th, three seconds behind the leader and within a second of the 5th through 8th-place cars. He had already reached an agreement to drive sports cars for Carroll Shelby's, Cobra organization, and admitted Honda was asking him to clear his schedule for all Grand Prix dates in 1965. If, as the song says, "It's a long, long time from May to December," for Ron Bucknum it had been several light-years from March to September. . .

In all of Grand Prix racing history there has been no exact parallel to Bucknum's rise from the ranks. Back in the Thirties, Auto-Union hired some drivers without race-car experience in order to start them fresh with a radically new design. But A-U did not rest all its hopes on such unproven entrants. For a man to come directly out of the relatively small-time arena of California club racing into the most demaming form of motorized competition in the world is extraordinary to say the least. One cannot help wondering what effect all this has had on the man himself: whether it worries him more than it reassures him, whether he gains confidence from it or is humbled. In Ron Bucknum's case, a little of each seems to be true: He has undoubtedly lost a certain amount of equilibrium (as any man might, under the circumstances); he is fighting hard to recover it. He seems fully aware how unusual (unlikely, even) his leap has been, and yet his belief in his own ability is at war with this realization. He senses he has been struck by lightning but he wants and needs to believe the lightning had to strike . . . that it was just a matter of time. And he can be aggressive about this, or defensive, depending on circumstances.

"I used to get awfully annoyed when people would come up to me - people I'd known back home-and say, 'What the hell? One minute you're driving an MG, and the next time I see you you're in Formula 1. Is it that easy?' I'd remind them I did drive modifieds a few times-and incidentally, the experience I got with '01 Yaller' was invaluable I never could have made it with Honda otherwise.' And I wasn't exactly unknown in the States, after all. Then I got to where 'I'd just say, 'Oh yeah, there's nothing much to it,' just play along with them, you know. It doesn't bother me anymore'?'

But it does.

Three or four rides in a modified car-even so potent a one as a Max Balchowsky "01' Yaller" - do not constitute much real experience, and victories in production cars seldom earn more than local repute. Bucknum knows this and knows the question~ "Why you? Why not someone else?" is not answered by such considerations. He is willing to discuss the subject and does so with surprising objectivity:

"Don't think I haven't asked myself the same question plenty of times. I have. I'll tell you what happened, and what I think about it, and you can draw your own conclusions. . .

"First of all, Japan has never raced GP before, so it doesn't have any drivers of its own who'd' be disappointed. Second, the U.S. doesn't build a GP car, so Honda wouldn't step on any toes hiring an American. Now understand, there are good reasons why the company may have wanted an American driver-it sells a lot of motorcycles in the States, it wi1l sell a lot of the new 'Six-Hundred' sports cars here too, so the publicity will be good. And, of course, the best market for both products is Southern California.

"Okay, that narrows it down to an American, and someone from the-Los Angeles area if possible. Now, I've heard they went around to a number of people, people connected with West Coast racing, and asked for a list of four names, two experienced drivers and two who were, well, I guess you'd say 'promising.' I don't know who all they asked; I know they asked Les Richter, competition director at Riverside Raceway, . because he told me; I don't know about the others." He thought a minute, then added, "Of course, I had a couple of pretty good races in the MQ about that time .

"That made it a question of whether they'd hire me, or the experienced driyer most people named, Phil Hill. When I talked to him at Sebring, early this year, he was trying to decide what to do he'd just been offered a contract by Cooper and I guess he thought his chances would be better there."

So far as it goes, Bucknum's assessment of the situation seems both accurate and reasonable. However, almost as interesting as his explanation were the things he did not say. He did not say, for instance, that Honda might have chosen an inexperienced driver so that in case its early efforts weren't successful some of the blame would fall on the driver. This is something almost everyone else has said, he must know it, and it must represent one of the greatest pressures riding on him. He did not mention it. He did not, for that matter, mention that there was anything out of the ordinary in his having been considered in the same light of candidacy with the former World Champion - or that he might have been lucky that Hill decided to go with Cooper. If he feels any of these things, he has kept them to himself.

It rained Saturday at Monza, a light sprinkle beginning just past noon, growing heavier as time for the Formula I session approached. Buckmim wished it would stop.

"I never used to mind it in production cars," he said, "but in a Formula I it's different. It's like driving a Volkswagen, full speed, on ice. I get the feeling that if I came to a complete stop, and got out of the car, it would just slowly sli-i-i-de off the road, and into a ditch. Of course, no one likes the rain in a GP," he added quickly. "Moss used to say he liked it, but he just did that to psych the other drivers as he himself admitted to someone after he'd retired from competition."

Bucknum's only serious sports car accident had, occurred in the rain, at the Pomona track in California. He'd been driving the AC Bristol at the time.

"We were coming down to turn one, at the end of the straightaway, and we'd slowed to about 30 miles an hour. Some guy whose goggles had gotten fogged up didn't see the turn. He didn't even slow down, and he hit me at about 130, and went right over the front end of my car. I wasn't hurt, though, and other than that I'd never had a crash until Nurburg. "

He left the road at Nurburg Ring, near the Karussell, after putting up a fine performance for 180 miles on the wet, tortuous road.

"The steering let go," he says, and adds, "at least that's my story-it isn't Honda's. But I came up to the corner and turned the wheel and absolutely nothing happened. I remember thinking: 'Oh-oh, Bucknum, here you go - and flew straight off the track. I thought at the time I'd hit a great big puddle of oil, but I checked after I got out and the track was dry. Of course the front end of the car was demolished, so you couldn't really tell, but I'm certain something in the steering failed. Anyway, I came out lucky, something tore through c my pants and cut my leg a little, but that's all."

Nancy had been at the track that day, having left 3-month old Kathy with friends in California in order to attend this premiere event.

"At first she thought I'd just run out of gas. We'd expected to get quite low, and she told me later she'd actually turned to someone and made a joke about it when I didn't come around for - number 13. Well, when she saw me and realized I'd crashed she was pretty shaken up.

"She's never objected to my racing, though. I was racing when we met, and I think she's always known what it meant to me. I'm not saying she wouldn't be happier if I were doing something else, but. . ."

He spoke then, as a Grand Prix driver, of the advantages and disadvantages of having a family.

"It can be rough on kids, all the moving around and everything. We plan to settle in London next year, which is close enough to everything that we won't have to be apart so much.

Overall, I think having a family is good for a driver, it settles him down and makes him think about the future. It keeps him from being alone so much, too, and that's one of the toughest parts of this business," he added.

"This is a 'gypsy' life, you know, all the running around you have to do. Most of the drivers have their own little hideaways around Europe and you don't see much of them between races. Since Nancy went back, after Nurburg Ring, I've really felt it. I guess my biggest personal expense these days is telephone calls. I call home about twice a week, and we talk for 20 minutes or so, and it really runs into money. I'd like to go home after every race, but you can't. The company pays your way to the GPs, plus one trip a year to Europe and back, and that's all.

"But a driver can do pretty well in the business if he's careful with his money. I got a good figure for signing with Honda, I get paid for each race I start, and get a share of the winnings. There's quite a bit in signing with parts manufacturers and suppliers, and you can pick up extra on the side from racing sports cars. Honda's been very good about that, incidentally, figuring any outside experience I can get is to the good. I have some investment plans for part of what I make, but I don't want to talk about that just now.

"My future? Well, you know what happened in motorcycle racing. Honda took an unknown driver and won the championship with him four times. I think Honda's in GP racing to stay; the company is in it to win and I think it will win."This could, of course, mean the championship for Bucknum as well. During final practice, in the rain, Bucknum was 8th fastest, but since everyone had been slower than on Friday, he started 9th in the race itself. The car staggered on the starting line and took off last. By the second time around he'd caught and passed four cars, and a short while later he was running close behind the pack. He picked off one or two stragglers, then crouched, sprang-and passed Lorenzo Bandini (Ferrari), Richie Ginther (BRM), Jack Brabham (Brabham), Joe Bonnier (Brabham) and Innes Ireland (BRP) . . . All in one lap.

The following lap the brakes failed and it was decided to retire the car. (There are circuits which can be driven reasonably well without brakes, but Monza isn't one of them.)

In all it had been an incredible performance. True, the steering had apparently gone at Nurburg, the brakes at Monza - par for a new automobile. But it's worth noting there was nothing wrong with the steering at the Italian GP and, knowing Honda, it's a good guess there'll be nothing wrong with the brakes at the next event.

The one factor which is difficult to read is the personal factor of Bucknum himself. That he has the ability is beyond doubt, but it is also true that he is attempting one of the most abrupt transitions in the history of the sport.

The pressures are enormous, and there are some new ones to come.

Honda has prepared and entered only one car at a time this year (the one at Monza was completely new, the Nurburg car having been damaged beyond immediate repair) on the excellent theory that, because the team would make some mistakes at first, there was no point in duplicating them. But Honda can be expected to field a full team in 1965. It will be hiring more drivers, experienced ones in all probability, and it remains to be seen how Bucknum will respond to a challenge from within his own organization. He may profit from such associations, or he may not. He may be willing to follow when necessary, or he may feel compelled to lead at any cost. Only a little more time will tell.

So far, the indications are good. He expresses pleasure at the way the other drivers have accepted him into their ranks, which of course means that his own attitude has been right. He admits and talks freely about the help he has received from others (Phil and Richie in particular) in learning the circuits. He seems to be moving toward a better understanding of the problems he must face, and an acceptance of them.

Sunday night at dinner Jim Redman came over to the table. Redman is the man who has won four World Championships on Honda motorcycles. During the meal he told of a near scrape he had in a race on the Isle of Man. It seems he'd been following a rider at extremely close range, seen a tiny puff of smoke from the other's engine, and turned aside just in time to avoid a crash at over 120. Later, Ron commented on the story: "It just goes to show the difference between youth "and experience," he said. "Now, Jim's been around long enough to have known that little puff meant the other guy's engine had frozen. It probably saved his life. Of course a younger man with faster reactions might not have seen the smoke, or known what it meant, but he might have been quick enough to get around anyway."

Aside from the fact he didn't seem to know he was talking about himself and his own hopes for overcoming lack of experience, the comment indicated that he has not taken the problem lightly, that he is thinking about it a good deal, and working toward a solution within himself. His chances strike me as excellent.

He's off to a good beginning, with the ambition, the skill, and the automobile.

Ron Bucknum and Honda-champions of the world in 1965? Who knows? But if you're. planning to bet against them, get good odds.

Author: ArchitectPage