Swedish

1930-72 written in '72

JOAKIM BONNIER died at Le Mans this year (72), driving in a race he disliked and thought unsuitable for Grand Prix drivers. Paradoxically, he was extremely good at long-distance racing but disapproved of "endurance tests" such as Le Mans and the Sebring 12 hours. Indeed, there were many paradoxes in Jo's personality, life and career: He would never have been a poor man, having begun life in Stockholm in January 1930 as a member of a family which owns a paper-making and publishing empire.

He was educated in Sweden and at Oxford, he spoke fluent English, German, French and Italian as well as his native tongue, and with his good looks, his dignified presence and charm, he could have been anything he chose. He chose to be a racing driver.

Jo began his career in Formula 1 in 1956 and was at the time of his death the only active driver who had raced against Collins, Hawthorn, Moss, Fangio and the other heroes of the Fifties. For some reason which even he had forgotten, he made up his mind to be a racing driver at a very early age. He started riding motorcycles as a teenager and then followed what has become almost a standard course for Scandinavian drivers, charging sideways through snowy forests in sedans. Jo claimed you could learn more about controlling a car that way than in many years of circuit racing. He had something of an obsession, for want of a better word, with the idea of being in control of this violent chunk of metal called a motor car.

His fatal accident that came at Le Mans while he was driving his 3-liter Lo1a-DFV T280 was not caused by mechanical failure. He was overtaking the slower Ferrari Daytona of Florian Vetsch at Indianapolis corner when the two cars touched and the Lola vaulted over the guardrail into the trees and disintegrated. Opinion is divided as to whether Jo made an error in judgment, trying to pass at just that time, but no blame has been attached to Vetsch and I think the only answer is that was purely one of the hazards of motor racing-an unfortunate accident.

Jo knew all about hazards and accidents. He was above all others who fought for years to make racing safer for drivers. His was almost.a one-man campaign until Jackie Stewart joined the fight.

His long career as a racing driver began with a rally in Sweden in 1948. He then spent three years in the Swedish navy as a lieutenant and when he returned home he took up ice racing and rallies, first in a Citroen, later in Alfa Romeos. The Alfa factory gave him the ex-Fangio Mille Miglia Disco Volante to drive in international events, which introduced him to the wider world of motor sport. He added an Alfa Giulietta Sprint and a 1.5-liter Maserati sports car to his stable and, with McKay Fraser, traveled to the Ellropean races. His first Formula 1 drive came rather suddenly at Monza in 1956 when he was asked to replace Villoresi, who was ill.

Never before had he driven a single:- seater but his tenacity must have been impressive as he became a member of the Maserati team for 1957. In 1959 he moved officially to BRM and great was their joy when he won the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort after battling with Moss and Brabham throughout.

This remained the high point of his career and why he never quite reached that pitch of combined talent, good fortune and car reliability in Formula 1 again is impossible to analyze. Jo drove for BRM for another year but scored only two fifth places in Grands Prix. At the same time he was driving sports cars for Porsche and thence to the Porsche Formula 1 team in 1961 and 1962. This combination might have become formidable if Porsche had continued in Formula 1 but they pulled out and for years thereafter Jo ran a succession of privately entered Formula1 cars of various makes. His best results were now to come in sports car racing, however. He won the Targa Florio twice, once in 1960 and again in 1963. He took the Sebring 12 hours for Ferrari in 1962, the Reims 12 hours and the Paris 1000 km in 1964 and in 1967 the fame of the Cqaparral echoed round the world when he co-drove one to victory with Phil Hill at Nurburgring.

After 1967 his name was linked with Lola, for whom he was the European distributor, and since 1970 he had more success with these 2-liter sports cars than in his various Formula 1 drives. He retired from Formula 1 in 1971 and hung. his last car, a McLaren M7C, on a wall of his home as a memento and as a work of art.

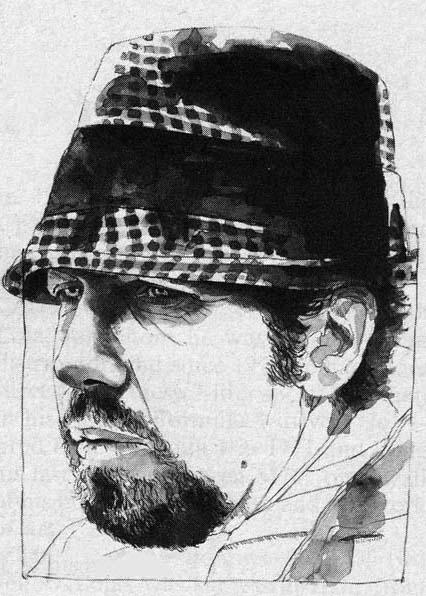

This year the Bonnier team of two yellow Lolas was successful right from the start at Buenos Aires and he had led the 24 hours in the early stages. He was running 10th after several pit stops when he was killed. But it is not only for Jo's racing successes that he will be remembered. What will also be missed is his dignity, his tall, fur-coated, dark-bearded figure wandering aloofly around the paddocks of the world, his impeccable manners, his sense of humor, his earnest desire to be accepted.

The paradoxes appear again. He loved motor racing and thoroughly enjoyed pitting his strength and wits against the car and the elements. But on entering his home there was little sign that it belonged to a racing driver. His pretty, blonde Swedish wife, Marianne, has the same air of good breeding as Jo and has always been as good a hostess as he was a considerate and enthusiastic host. Their home at Les Muids, Geneva, overlooking a sunny terrace, the Lake of Geneva and the snowy Alps, is enormous, beautiful, comfortable and gracious. It could be set down anywhere in the world and still announce its good taste and style. The two young Bonnier sons, Jonas and Kim, are blond, tanned, multi-lingual and polite.

At this home, Le Grange, there was peace, luxury and, heading it all, a man who could talk about an immense range of subjects with authority. He was part owner of an art gallery in Lausanne for some years and was interested in good and lovely things, both antique and modern.

Yet he couldn't stop driving race cars because he enjoyed it so much. It is easy to say, "What a pity he didn't retire before." Of course it is a pity and I feel sorry (or the gentle Marianne and her two children. But it was Jo's life, he had seen more drivers killed than most of us, he knew all the dangers and had fought against the less necessary of them. He was the only true motor racing diplomat. He will be missed much more than most people would have expected.

Author: ArchitectPage