LOTUS

Colin Chapman's marque was in the forefront of racing for many years, in terms of technical innovation and successes on the circuits, and it also went through periods of failure as well as triumph. After his death in 1982 Team Lotus was kept in racing by his lieutenants, but save for an innovation that in fact had its origins in Chapman's days it tended to have the status of one of several constructors' teams. The 1980s ended with the team at a low ebb - it contested its 400th Grand Prix in 1989, but without adding to the victory score of 79 that had been reached in 1987 - and in some disarray, but that hardly dimmed the brilliance of the past.

Chapman's first single-seater might not have been a Lotus, but a design commissioned by the Clairmonte brothers for F2 in 1952 (it was completed as a sports car). He also worked as a consultant for Vanwall and BRM. The first Lotus single-seaters were never successful in their front-line days, and Chapman had to accept that a rear engined layout was the right one. Once he did his Lotus cars became pace setters, and until 1971 Lotus was a leading company in the customer car market as well as in its racing teams.

Lotus teams and Lotus private entrants became leading contenders with the 18, and its successors. Innovations included the monocoque principle, introduced with the 25 and to become universal. Chapman was also instrumental in getting Ford backing for the Cosworth DFV engine to power his Fl cars, and in time they were to power every car in F1 except odd Italian machines. He might not have invented 'wings' but he led the way in pushing that branch of automotive aerodynamics forward, almost beyond the point of understanding, as he did with ground effects. From the mid 1960s his ideas were translated into working designs by men like Maurice Phillippe, but he invariably provided the inspiration.

Lotus stopped making customer racing cars in 1971, and from that time the story of Lotus racing cars is the story of Team Lotus. That was usually coupled with a sponsor's nameGold Leaf Team Lotus in the great days of the 49 (sadly near the end of the great Jim Clark's career). Chapman, perhaps unwittingly, set formula racing on the road to sponsorship that was to become virtually universal. He did not heed the traditionalists when they failed to see that racing was heading towards an expensive new age of high technology. He was not, however, entirely blind to history and by the early 1980s had gathered together a collection of past Lotus models. Among them were many that were outstanding by any racing yardstick: in the world of Grand Prix racing, Lotus won the Constructors' Championship seven times and finished in the top three on the points table 18 times in the years 1960-87.

After Chapman's death his team continued under its manager Peter Warr, who had joined Lotus in 1958 and managed the Grand Prix team in the 1970s before a brief spell with Wolf and Fittipaldi. The long-standing association with Players, which apart from a brief period in the 1970s had run from 1968, finally ended in 1986. In the following year there was the shock of seeing Lotus GP cars in bright yellow Camel colours. Moreover, they brought 'active' suspension into Grand Prix racing, apparently successfully as the 'active' cars won two Grands Prix. But that was to be the last flash of success in the 1980s.

Designer Ducarouge perhaps lost his touch, and things did not go well on the circuits in 1988-90. This led to schisms, and the situation was not improved as drivers and car failed to live up to expectations. The Chapman family, which still controlled the racing team, took action. Team director Peter Warr left and Tony Rudd was seconded from the main Lotus company to become Executive Chairman of Team Lotus International.

12 The first single-seater Lotus as such appeared at the 1956 London Motor Show, but the winter passed before circuit tests were run with a 12. This F2 car seemed as small as a front engined formula could be. It was built around a lightweight space frame, initially with a double wishbone front suspension and a de Dion arrangement at the rear, soon to be superseded by 'Chapman strut' suspension (a substantial hub casting, long coil spring/shock absorber, radius arm and half shaft). The engine was the Coventry Climax FPF, mounted rigidly and angled down towards the rear to drop the height of the propshaft as it made its way to the Lotus gearbox that was to cause much heartache. The body design emphasised low frontal area and sleekness.

The inauspicious race debut of the 12 came at Goodwood at Easter 1957, Allison retiring as a half shaft failed. A few weeks later Mackay-Fraser recorded the first finish for a single-seater Lotus, second in a short Brands Hatch race.

In 1958 Lotus grew into the Grand Prix world as 12s were run as Fl cars, with 1.96-, 2.0- and 2.2-litre FPFs. Hill made the first race start in an F1 Lotus, in the Silverstone International Trophy, and Allison and Hill started 2.0-litre 12s in that year's Monaco GP, when Allison was sixth (and last). Some 12s served F2 independents into 1959.Drivers: Cliff Allison, Graham Hill.

16 This was a more sophisticated design, outwardly sleeker than the 12 and with a cross-section that appeared nearer to oval than round. The space frame was lightweight to an extent that equated with fragility, suspension followed 12 lines, while in the interests of minimal frontal area the FPF was inclined (at varying degrees) and offset to the centre line so that the transmission ran 'to the left of the cockpit.

The 16 appeared in F1 and F2 forms, both being raced for the first time at the 1958 French GP meeting, running alongside the 12. Team Lotus record was far from outstanding: Allison was the fifth F1 finisher in the German GP, but a pit stop had cost almost 20 minutes and overall fifth place had been taken by Mclaren in an F2 Cooper, so Hill's fifth in the Italian GP was the best actual F1 result. 1959 was little better, although Ireland was fourth in the Dutch GP and was classified fifth at Sebring. The 16s made few appearances in 1960, several went to Australia, some were cut and shut for various purposes, and in the 1970's some found reliability in historic racing.

Drivers (Ft): Cliff Allison, Graham Hill, Innes Ireland, Rodriguez Larreta, Pete Lovely, David Piper, Alan Stacey, Mike Taylor. )

18 The first mid-engined Lotus was a chunky car, built around a space frame that was stouter and less complex than the 16's but weighing only a little over 27kg (and fibreglass bodywork added little to that). The suspension used unequal-length wishbones at the front, with a single lower wishbone and fixed-length drives haft at the rear, with twin radius rods. On the 'senior' versions Lotus' gearbox was used, for FJ versions VW- or Renault-based 'boxes were specified. This Lotus was built for three classes - F1 and F2, with Climax engines, and Formula junior where the modified Ford lOSE rated at 75bhp in 1960 was the usual power unit. A handful of FJ cars were run with BMC A-series engines and Mitter installed one of his DKW engines in an 18. There were of course other differences, for example in fuel arrangements. In the F1!F2 cars there were many independent variations, for example the Walker cars had revised transmission, in an experimental Vanwall engine was installed in an 18, and Borgward and Maserati engines were also fitted. There were a lot of these cars around - in 1960 no fewer than 125 FJ 18s were turned out - and there was presumably some 'interchange' between chassis.

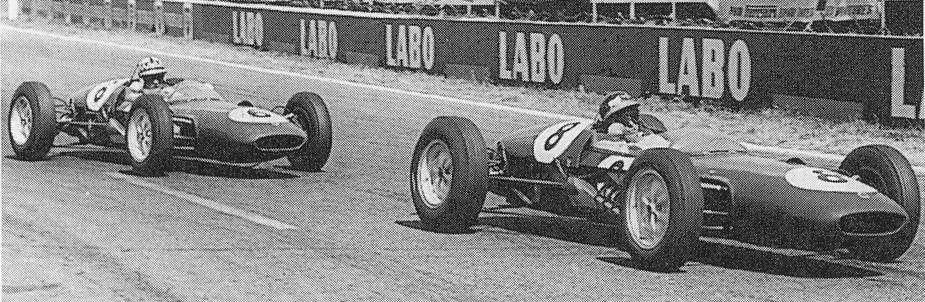

The FJ version came first, at the 1959 Brands Hatch Boxing Day meeting, and within weeks Ireland led the Argentine GP in an F1 18, before falling away to finish sixth. At Oulton Park at Easter Ireland drove an 18 to score Team Lotus' first F2 victory, and on the Easter Monday won both the F1 and F2 races. Then at Monaco Stirling Moss drove Walker's 18 to score the first GP victory for Lotus. In the Constructors' Championship that year Lotus was runner-up to Cooper. In 1961 Lotus was runner-up to Ferrari, in large part due to Moss' efforts in Walker cars. These were 18s with sleeker bodywork as clashing supplier contracts meant that Lotus could not supply the latest model (the 21) to Walker. Other independent cars were similarly modified, and usually referred to as 18/21 (a Walker 18/21 had a Climax V-8 fitted).

Meanwhile, the 18 had been overwhelmingly succtessful in FJ racing, and in the last season of the 1.5-litre F2 four races fell to this milestone car.

Drivers (Fl18 and '18/21'): Carlo Abate, Cliff Allisqn, Gerry Ashmore, Lucien Bianchi, Jo Bonnier, Ian Burgess, John Campbell-Jones, Ron Carter,Jay Chamberlain,Jim Clark, Colin Davis, Graham Eden, Ron Flockhart, Olivier Gendebien, Masten Gregory, Dan Gurney, Bruce Halford, Jim Hall, Carl Hammarlund, Walt Hansgen, Gary Hocking, Innes Ireland, Kurt Kuhnke, Tony Maggs, Willy Mairesse, Ernst Maring, Tony Marsh, Michael May, Stirling Moss, Olle Nygren, Tim Parnell, Andre Pilette, David Piper, Ernesto Prinroth, Phil Robinson, Lloyd Ruby, Jock Russell, Pete Ryan, Giorgio" Scarlatti, Wolfgang Seidel, Gunther Seifert, Tony Shelly, Alan Stacey, Gaetano Starrabba, John Surtees, Henry Taylor, Mike Taylor, Trevor Taylor, Maurice Trintignant, Nino Vaccarella.

20 An FJ car introduced at the 1961 London Racing Car Show, the 20 was as slippery as the 18 had been square. The driver was seated in a semi-reclining position, a finer nose line was achieved by moving the fuel tank back to behind the driver's seat, smaller front wheels were used, brakes were inboard at the rear (and the 20B had discs in place of drums). Quoted power output of the usual 1098cc Cosworth-Ford lOSE was 85bhp. This was another highly successful car, in a very competitive category, and 118 were built.

21 This was an interim car, deriving from the 20 and used to hold the line while Lotus (and other teams) waited for Britsh 1.5-litre F1 V-8s. The familiar FPF was used, driving through a ZF gearbox. It was obviously stronger than the FJ car, and other differences included increased fuel tankage, the use of inboard coil spring/shock absorber units at the front and outboard brakes at the rear.

Race debut for the 21 came at Monaco, but the highlight for Team Lotus came at the end of the season when Ireland scored its first Grand Prix victory, at Watkins Glen. He also won two non-Championship races in 21s, yet at the end of the year was dismissed by Chapman. Jim Clark and Trevor Taylor had a rewarding late year expedition to South Africa with 21s, winning four races (several 21s were used by South African independents through the following years). Single cars were briefly used by the Brabham, Filipinetti and Walker teams.

Drivers: C. Barrau, Jack Brabham, Jim Clark, Jim Hall, Innes Ireland, Neville Lederle, Willy Mairesse, Gerhard Mitter, Stirling Moss, H. Muller, E. Pieterse,Jo Siffert, Trevor Taylor.

22 The 1962 FJ car was once ~again announced at the London Racing Car Show (then a significant pre-season showroom for Lotus Components, responsible for car sales). It was a further refinement, primarily with an inclined engine, almost invariably a MkIV Cosworth-Ford although Mitter again chose DKW power (sic) for his Lotus. As in 1960 (with Clark) and 1961 (with Trevor Taylor) a Team Lotus driver dominated the season - Peter Arundell started in 25 races ii1'22s, won 18, was placed second in three and retired four tim,es. Niemann ran one in F1 guise, with an enlarged,Cosworth engine, in South Africa in 1963-4.

24 Seemingly introduced as an improved 21 space frame car to take either of the new British 1.5-litre V-8s - until in May 1962 it became obvious that for Team Lotus it was a stand-in and that it was actually a customer car. Of the dozen turned out by Lotus, seven eventually had Coventry Climax FWMV V-8s, five had BRM V-8s; Parnell built up additional cars.

The 24 was used by Team Lotus until superseded by 25s. Other leading teams which ran 24s were Walker, UDT-Laystall, Brabham and Bowmaker/Parnell, and 24s appeared on F1 grids through to the end of 1964.

Drivers (Fl): Chris Amon, Peter Arundell, Mike Beckwith, Jimmy Blumer, Jo Bonnier, Jack Brabham, John CampbellJones, Jim Clark, Bernard Collomb, Paddy Driver, Masten Gregory, Mike Hailwood, Jim Hall, Graham Hill, Phil Hill, Innes Ireland, Tony Maggs, Tim Parnell, Roger penske, Peter Revson, Hans Schiller, R. Schroeder, Wolfgang Seidel, Gunther Seifert, Hap Sharp,Jo Siffert, Trevor Taylor, Maurice Trintignant, Nino Vaccarella, Heini Walter, Rodger Ward, Andre Wicky.

25 This was a most significant car for, avoiding discussion of aircraft and car precedents, with it Chapman introduced monaca que chassis construction to Grand Prix racing. By modern standards it had a simple bathtub structure, with twin side pontoons in light alloy sheet linked by steel bulkheads fore and aft, the instrument panel and the undertray, but it established the principle., It was light, at just under 30kg, yet offered a high degree of stiffness which was to pay dividends in cornering powers as a more supple suspension set-up could be used., It was also a major contribution to safety. Suspension followed the 24 and the Climax FWMV was the normal engine, although some cars were to be re-engined when they were sold out of the works team (for example, Parnell's pair had BRM V-8s, and Hewland gearboxes in place of the ZF originals).

All seven built first served with Team Lotus, and those still on the strength in 1964 were uprated to 25Bs, with smaller wheels and revised suspension. Further detail modifications followed, and in effect Len Terry developed the car as the 33.

A 25 was first raced in the 1962 Dutch GP, and Clark scored the first victory with one in Belgium a month later. The team used 25s through 1964, ,when a broad yellow stripe was added to the green of the fibreglass bodywork, following the colours used on the Lotus Indianapolis cars in 1963. Independents used them into the second year of the 3-litre formula, with four-cylinder Climax engines or enlarged BRM V-8s.

The Team Lotus 25s won 14 Championship races. In 1963 Clark drove them to win his first World Title, with seven race victories, and that year Lotus won the Constructors' Championship for the first time.

Drivers: Chris Amon, Peter Arundell, Richard AttWood, Giancarlo Baghetti, Bob Bondurant, Jo Bonnier, Jim Clark, Piers Courage, Mike Hailwood, Paul Hawkins, Innes Ireland, Chris Irwin, Tony Maggs, Gerhard Mitter, Pedro Rodriguez, Giacomo Russo, Moises Solana, Mike Spence, Trevor Taylor.

27 By general consent, FJ had become unrealistically sophisticated and costly by 1962, and for the following season Lotus seemed to hasten the category's demise by introducing a monaca que FJ car. This was actually intended to prove the construction for secondary category customer cars for 1964, when new F2 and F3 regulations were to come)nto force.

The first monocoque, however, had fibreglass sides which lacked rigidity and it had to be redesigned in alloy. The delay meant that there were few customers, and the quasi-works cars run by Ron Harris' team were not developed and~inning until the summer (Arundell won half-a-dozen leading races on the trot, to just beat Hulme to the British Championship).

31 Lotus' first car for the I-litre F3 was a space frame design deriving from the FJ 22. Only a few were sold in a half-way house season, when many contenders used sleeved-down FJ engines and, as far as Lotus was concerned, 20 or 22 chassis. Only one major FJ race fell to a Lotus (and that was aJanspeedBMC powered 20/22, driven by Fenning at Silverstone), but then the season was dominated by the combination of J.Y.

Stewart, K. Tyrrell, and Cooper. An 'improved version' was offered for 1965, alongside the more expensive 35. The design was later revived as the Mk51 FF 1600 car.

32 For the new I-litre F2, Lotus based a car on the monocoque 27. The tub was in steel, with room for a 41-litre fuel tank in each flank. Suspension was modified, and fully adjustable (that overcame a shortcoming in the 27) and the 115bhp 998cc Cos,worth SCA was canted at an angle of32 degrees, which led tOia~ slightly offset Hewland gearbox/final drive and unequal length driveshafts. Harris ran four cars (of the 12 built) and his drivers won seven races in a season when Brabhams were the cats to beat, Clark taking six and Stewart one. A 32B version with a 2.5-litre Climax engine was built for Tasman racing, and driven by Clark to win five races in early 1965.

33 In effect this was a development of the 25 - the chassis numbering sequence continued from that model - with the the new wide Dunlops, modified suspension and numerous detail changes. It first appeared in the Spring of 1964, and from the summer started to take the place of the 25s in the Team Lotus line up. In 1965 it was the mainstay, and continued to be run through the first season of 3-litre Grands Prix, with 2litre 32-valve Climax V-8s or 2.1-litre BRM V-8s, alongside the 43 with its cumbersome BRM H-16.

Clark and Lotus won the Championship in 1965, with six Championship race victories, but finished well down both points tables in 1966. In the following year Clark won the Tasman Championship with a Climax-engined 33. Once the 49 with the DFV engine arrived in 1967 there wasHJtle life in the 33s, even for independents, and the cars disappeared from main-line racing very soon after the last Team LotllS race:with them, at Monaco in 1967.

Drivers (GPs): Peter Arundell,Jim Clark, Walt Hansgen, Paul Hawkins, Graham Hill, Pedro F-odriguez, Giacomo Russo, Moises Solana, Mike Spence.

35 F3 was more popular in 1965 but there were few customers for the monocoque 35, which was in a line of evolution from the 27 and 32 and also doubled as an F2 car. Chassis and suspension were standardized, and the 35 would accept a wide range of engines and gearboxes (Cosworth MAE or Holbay engines were the common F3 types, Cosworth SAE or BRM units in F2, with Hewland four-, five- or six- speed 'boxes). In either guise it was a slim car, and looked the part. In 1965 Ron Harris ran' cars in both classes; Clark won the British and French F2 Championships for this team, but in F3 the only bright moment came when Revson won at Monaco.

39 An F1 design for the Coventry Climax FWMV flat sixteen, which was never raced as the FWMV proved equal to '1965

challenges - as Clark's achievements with the 33 showed. The

chassis of the 39 was adapted for a 2.5-litre Climax FPF (a first Lotus design assignment for Len Terry's successor, Maurice Phillippe). Clark drove the 39 in the 1966 Tasman series, without 'great success.-XC

41 This F3 car marked a determined fight back into this market in 1966. In it Lotus reverted to a space frame, although the tubes were stiffened with sheet metal diaphragms (foot box, dashboard, rear of cockpit, gearbox area) and undertray. The engine (a Cosworth MAE) was inclined at 30 degrees and like the gearbox was mounted to contribute to rigidity. The unusually wide track almost drew attention to the slim body - in spite of the tubular structure, the 41 had less frontal area than the 35.

A quasi-works team was run by Charles Lucas, WhOSE drivers Courage" and Pike won half a dozen races, deritin~ Brabham superiority. But above all, this was a customer car; ar, initial batch of 34 was laid down (price £2475 assembled!) and final production reached 61. The 41B was an F2 version with an FV A engine, and the number was also applied to the Formula B version in 1967. That year also saw the 41C F3 car with revised suspension, but the sales response was poor as. the 41s had gained a reputation for fragility. The '41X' was a one-off derivative with a pronounced wedge body, which Gold Leaf Team Lotus driver John Miles used to score several victories in 1968, when it was modified and became the 55.

43 For an interim 3-litre F1 engine Chapman had to turn to the over-complex and heavy BRM H-16, which was used in a pair of 43s. It was a stressed member" carrying the rear suspension, and it was mounted to a bulkhead behind the cockpit. The short monocoque followed lines laid down in the 38 USAC car. A 43 first appeared in practice for the 1966 Belgian GP, and that car was the only 43 to finish a race, when Jim Clark won the 1966 American GP. A second was completed (a pair started in only one GP, in South Africa in 1967), then the 43s were soldfor independent conversions to F5000.

Drivers: Peter Arundell, Jim Clark, Graham Hill.

44 The F2 car for 1966, based on the monocoque of the 35 with the wi,de suspension of the 41, and with Cosworth engines that were no match for Brabham's Honda units. Three were used by Ron Harris' team, for which Clark and Arundell were in distant third and tenth places on the Championship table; the third car was driven by several drivers.

48 A new car for the new 1.6-litre F2, although it was first used in the Australian GP. It had a full monocoque, with a tubular sub frame for the Cosworth FV A engine. In 1967 Clark won three races, against another Brabham tide, but his team mate Graham Hill could do no better than two second places.

The cars were brought out again in 1968, and because there were no F1 cars available at the time of the presentation one of the 48s was the single-seater featured at the announcement of Gold Leaf Team Lotus. Clark, sadly, was driving a GLTL 48 when he was killed in a high-speed crash at Hockenheim.

49 This was a landmark car. After the uncertain first year of 3litre Grand Prix racing it set a true standard. It was laid out for the even more astonishing Cosworth-Ford DFV engine - Colin Chapman was instrumental in bringing together Keith Duckworth and Ford's Harley Copp and Walter Hayes, and they committed Ford to back the design and development of the DFV. It was to be exclusive to Lotus for the 1967 season, and the 49 was designed to complement it.

It was a straightforward car, with timeless lines in its first form. The cross-section of its monocoque was determined by the cross-section of the 90-degree V-8 (85.7 x 64.8mm, 2993cc), and this was bolted to the bulkhead behind the cockpit and served a load-bearing role. The rear suspension sub frame was bolted to the block and cylinder heads, with braking loads fed forward into the monocoque through twin radius arms. A dozen 49s carried chassis numbers, although three were rebuilds and one was an exhibition car and never raced. A 2.5-litre Cosworth DFW-engined version (49T) was run in Tasman races. The .49B of 1968 had a longer wheelbase, modifications in areas such as the rear sub frame, wider wheels and a semi-wedge body. Strutted 'wings' were carried from the French GP of that year, until both GLTL 49s crashed heavily as a result of rear aerofoil failures on the bumpy Barcelona circuit in 1969, when such devices were precipitately banned.

The 49 was driven by champions - Jimmy Clark won his 25th and' last Grand Prix victory in one, Emerson Fittipaldi drove his first F1 race for Lotus in one and Graham Hill won his second World Championship with 49s. It was in the front line for four years, at the centre ()f the great wings controversy, central to the introduction of sponsorship to Grand Prix racing, driven to a debut race victory by Clark in Holland in 1967 and the last of its twelve Championship race victories was scored by Rindt at Monaco in 1970. A 49 was the last private owner car to win.a Grand Prix, when Jo Siffert won in Ro Walker's 49n at Brands Hatch in 1968. The Lotus 49 was one of the great Grand Prix cars.

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Richard Attwood, Giancarlo Baghetti, Jo Bonnier, Bill Brack, Dave Charlton, Jim Clark, Emerson Fittipaldi, Wilson Fittipaldi, Graham Hill, Pete LQvely, Jackie Oliver, Jochen Rindt, JO Siffert, Moises Solana, Tony Trimmer, Eppie Weitzes.

55 The '41X' F3 car, revised and run as a GLTL entry in 1968.

56B The spare 56 from the 1968 USAC programme had a Pratt & Whitney gas turbine equivalent to a 3-litre piston engine installed in 1970, and it was raced in some F1 events in 1971. It was a four -wheel drive car, which suffered a variety of niggling setbacks, as well as throttle lag. Its first race was the Race of Champions, and in the Silverstone International TrQphy, on a more suitable circuit, it showed promise. Its best GP result was eighth in Italy, driven by Fittipaldi and run in black and gold colours, and its active career' ended when Fittipaldi finished second in a non-Championship race at Hockenheim.

Drivers: Emerson Fittipaldi, Dave Walker, Reine Wisell.

57 An F2 car with de Dion suspension that was tested in 1968 but never raced.

58 The 57 revised for further tests, with a Cosworth DFW engine ~ and ZF gearbox. If tests had shown worthwhile advantages the project might have been pursued for F1, as it was it never raced.

59/59B This design for F2 (59B) and F3 marked a Lotus effort to rebuild fortunes in the secondary categories."Dave Baldwin designed a fairly complex square tube space fraIlle, buqn the main the cars were orthodox. The body was notadfuired; and apparently was not very efficient in aerodynamic respects, but handling qualities were first class.

Roy Winkelman Racing :was the principal F2 team, worksblessed but without the status Ron Harris teams had in the past. Rindt and Hill were its 'name' drivers, arid the Austrian dominated in the 1969 F2 season.

There was a GLTL F3 team (drivers Pike and Nunn), while works help got 59s into the hands of other good drivers Kottulinsky and' Ikuzawa won with 59s, as did Emerson Fittipaldi - but in overall terms the season belonged to Tecno.

63 In laying out the complex 63, Lotus at least had experience of four wheel drive with the 56, and Phillippe followed that precedent in some respects. The car, of course, had much in common with the contemporary 64 Indianapolis car. The DFV was 'reversed' in the chassis, with the clutch behind. the driver's seat and the gearbox on the left, drive being taken fore and aft to ZF final drives. In components such as the fabricated suspension it was a substantial car by Lotus standards.

Regular 1969 team drivers Hill and Rindt did not like the 63, although ironically when Rindt was persuaded to race it, in the Gold Cup, he achieved its best result (second). John Miles drove it most, making five starts, and in nine races 63s recorded seven retirements.

Drivers: Mario Andretti,Jo Bonnier,John Miles,Jochen Rindt.

The odd overall appearance of the 63 does not call for comment, save that it was sleeker than other four wheel drive Fl cars. The bodywork' shows the upper line of the open bathtub monocoque. Rindt is the driver, at Oulton Park.

The 69 became popular in F3, and in 1971 Dave Walker was clearly the top driver - from 32 starts the single-car GL TL team scored 25 victories. That team did not contest F2 races, and in 1970 Rindt formed his own team with Bernie Ecclestone - in effect out of the Winkleman team - and he won four of the ten races he started. In the final year of 1.6-litre F2 racing, Emerson Fittipaldi won three European Trophy races in a Team Bardahl 69. With the 70, an unsuccessful Formula N 5000 car, these were the last Lotus production racing cars, and Lotus Racing Limited, which took the place of Lotus Components for 1971, ceased operations after a very brief life.

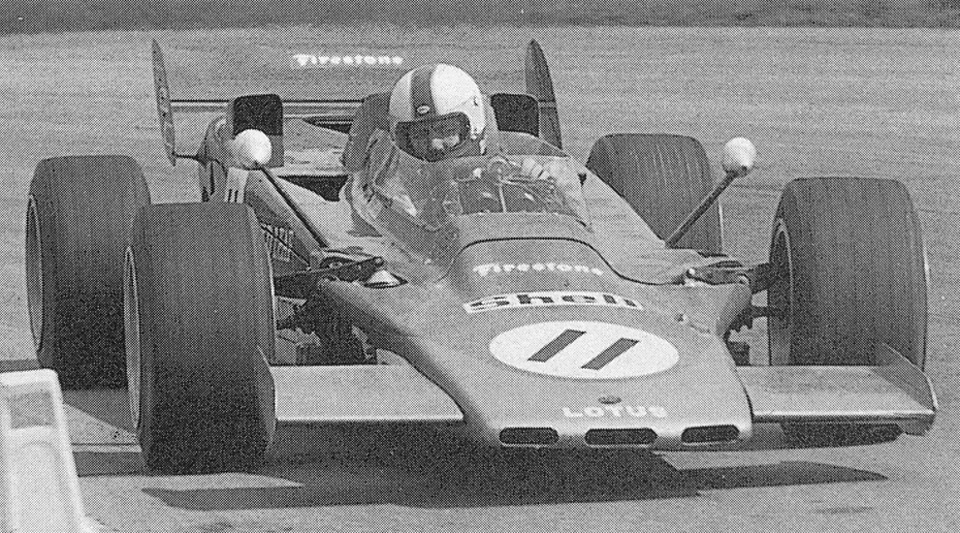

72 This successor to the 49 was also destined to serve longer than envisaged in the Grand Prix front line, although Chapman in no way saw this as a short - term car. He sought aqvantages over other teams using DFV engines land the cons::ept for Phillippe to turn into metal and fibreglass was radical - a refined wedge with radiators amidships and ultra low to enhance aerodynamic efficiency, with torsion bar rising rate suspension, and inboard brakes. Suspension loads were light and the tyres were well away from brake heat, so soft tyres could be used with grip advantages (problems did arise when Lotus switched from Firestone to Goodyear, and tyres that were not designed with the 72 in mind had to be used ).

The suspension was to be modified very early in the 72's career, when it looked as if the stunning car that had been drive, Dave Charlton ran one of the 1970 cars from 1972 (in the colours of another Cigarette company!) and two more went to South Africa. Odd 72s lingered on in minor British events in the late 1970s.

From 1972 the cars were run as John Player Specials, in black and gold livery. The 72 was first raced in Spain in 1970, and by the early summer was fully raceworthy - Rindt won the Dutch, French, British and German GPs in succession. Then in practice at Monza he was fatally injured in an accident that started when the right front brakeshaft failed. By finishing first and third in 72s in the US Grand Prix, Fittipaldi and Wisell ensured that Rindt's tally of points was not equalled and he thus became the sport's first posthumous champion.

The following year was largely barren, but in 1972 both Championships fell to the team (Fittipaldi taking the Drivers' title) and Lotus won the Constructors' title with the 72s in 1973. Peterson won three Championship races in 72s in 1974, but the car was slipping out of the front rank. There was little hope of victories in 1975, when the team concentrated on Peterson with the second carron for several drivers. The black 72s were last raced at Watkins Glen at the end of 1975, when Peterson placed one fifth. Nominally, nine of these handsome machines were built - there were rebuilds to the extent that new numbers would have been justified - and in six years the 72s added 20 Grand Prix victories to the Lotus tally. As early as 1970 a 72 had been sold, to Rob Walker for Graham Hill to unveiled might not be what it promised. Later the hull had to be redad to meet changing regulations, various 'wings' were used and from mid-1971 assorted airboxes were fitted. The first changes led to 72B, more early suspension refinements to 72C, the 72D had twin radius rods at the rear and subsequent modifications before the 72E in 1975 and then 72F which was longer and had coil spring rear suspension with 'helper' coil springs at the front.

The first 72, on the day it was first shown to the Press, at Hethe! early in 1970. NACA ducts took in cooling air for the disc brakes, 'chimneys' above them expelled that air and extractors were placed on them in pits after fast running to maintain a flow of air. driven by Fittipaldi at Monza in 1973. The radiator pods have been integrated into the deformable structure and a very large wing extends well behind the rear wheels.

Drivers (GPS): Dave Charlton,jim Crawford, Paddy Driver, Emerson Fittipaldi, Brian Henton, Graham. Hill, Jacky Icla, Eddie'l(eijan, John Miles, Ronnie Peterson, Jochen Rindt, Ian Scheckter, Tim Schenken, Tony Trimmer, Jack Tunmer, Dave Walker, John Watson, Reine Wisell.

73 This was an F3 car which according to the publicists was to complement the 72, a pair being run inJPTL black and gold colours. It had a monocoque centre section, with sub frames mounting the front suspension and the Nova engine/ transmission/rear suspension, side-mounted radiators and inboard brakes. It may have been advanced, but it was altogether too complicated for F3 and that led to lack of progress as the 1972 season wore on. One of the original pair was then used for Novamotor F2 engine tests and a 73B was developed late in 1972, but set aside as Lotus and the sponsors turned away from F3. In 1975 Dr Ehrlich acquired the 73s, running one late that year as an Ehrlich-Lotus.

74 The Texaco Star F2 cars, designed by Ralph Bellamy and using some features from the 72 - torsion bar suspension, inboard front brakes and hip radiators (water on the right, oil on the left). Lotus' 907 light-alloy engine was developed by Novamotor for this cat, to give a claimed 275bhp. Team manager 'Jim Endruweit had the driving services of Emerson Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson. On paper it was a winning combination but on the circuits a flop.

Although a CART Lotus was to be built in the mid-1980s it was never raced, so the 74 was the last Lotus single-seater to be raced by a works team/in a category outside F1.

76 Team and sponsor desperately wanted this to be known as the John Player Special, and the idea was an updated and lighter 72. Torsion bar suspension was retained, so were inboard brakes, and there was a novel electronic clutch (once the car started from rest, this could be operated with a gearlever button). It was, however, raced with a normal clutch and drivers preferred 72s. In mid-summer 1974 the 72 back end was grafted onto a 76 tub, and soon both 76s had 72 backs to make curious hybrids which were raced in late events.

Drivers: Jacky Ida, Ronnie Peterson, Tim Schenken"

77 The John .Player Special MkII' was a experimental car, eventually the product of the labours by several designers Geoff . Aldridge (monocoque) and Martin Ogilvie (suspension), with some input by Len Terry (suspension) and then Tony Southgate. Dubbed the 'adjustacar' it allowed for variations in track and wheelbase (facilitated as the brake callipers doubled as suspension pick~up points), while weight distribution could be changed. A driver-adjustable rear anti roll bar came in mid season and then skirts, to partly control under-car airflow. In all this the slim monocoque, DW and Hewland gearbox were almost overlooked.

Early in the year Peterson despaired and left, but Andretti committed himself to Lotus and through the year Nilsson gained in stature with the team. The performance of the 77 steadily improved, and at the end of the year Andretti drove one to victory in the Japanese GP.

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Bob Evans, Gunnar Nilsson, Ronnie Peterson.

78 A most significant Grand Prix car, theJPS MkIII established ground effects as a far-reaching development and put Team Lotus back in the forefront. But for some trivial reasons it would have been back on top. Once again Chapman laid down the principles, Bellamy, Ogilvie, aerodynamicist Peter Wright and others translated them into the car. It had a slim sandwich monocoque with wide side pods containing radiators, a fuel tank each, and the 'inverted wing section', with a skirt at the outer bottom edges extending down to the track to seal in the airflow (the skirt was a row of bristles on the first car, but rigid skirts soon came). The front track was wide, with suspension members interfering with the air flow to the side pods as little as possible. Andretti won four Grands Prix in 1977, Nilsson one. No drivers won as many as Andretti, no team won as many as Lotus, but both Championships eluded the team.

In 1978 Andretti and Peterson each won a GP before the 79 superseded the 78, but there was a sad footnote to the 78's career. Ronnie Peterson had to go. to the start of the 1979 Italian GP in one, as his 79 had been damaged in the warm-up session, and he was fatally injured in a start-line accident. Independent Hector Rebaque ran a 78 into 1979, and in that year the first 78 appeared in the minor British Fl series.

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Gunnar Nilsson, Ronnie Peterson, Hector Rebaque.

79 More than a refined 78, this was in many eyes the most elegant car of the 3-litre formula. It was an exemplary ground effects car, and it was a Championship car. Its side pods were wholeheartedly devoted to ground effects - there was a radiator in each (water on the right, oil on the left), but there were no fuel tanks in them as a single cell between cockpit and engine sufficed and the rear suspension was kept out of the airflow. In most other areas development was simple and although a Lotus gearbox built by Getrag and incorporating a freewheel was essayed, Lotus reverted to a Hewland FG400 for

~ the main season. The 79 was the car of the year, and it was reliable. Andretti won six GPs in 1978, one of them in a 78; Peterson won two (one in a 78) and was second four times.

Andretti was World Champion by a wide margin, and Lotus was clear winner of the Constructors' title.

In 1979 the 80 proved troublesome, and for mosLof the season Team Lotus had to rely on its 79s. Although prospects did not look bad as the season opened it soon became obvious that the pace-setting car of 1978 had been matched very quickly. There were points-scoring finishes, but no victories

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Jean-Pierre Jarier, Ronnie Peterson, Hector Rebaque, Carlos Reutemann.

80 An attempt to extend ground effects parameters, with side pods (and skirts) curving to continue inside the rear wheels. It even had skirts under the nose, but they were soon worn away and were replaced by a conventional nose with aerofoil winglets. The main skirts did not move up and down in their slides predictably, and if one jammed the ground effects seal could be broken, which could make life difficult for a driver. Andretti did place an 80 third in the 1979 Spanish GP, but this unhappy model was raced only three times.

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Carlos Reutemann.

81 A conservative approach made sense in 1980, and the 81 was a 'careful blend of the 79 and lessons learned from the 80' - according to the Press announcement. It was built around a basic sheet aluminium structure that derived from the 80, and a mid-season replacement monocoque led to the 81B designation. Elio de Angelis scored a second and a third early in the season, and there were a few other mildly encouraging performances (former team test driver Mansell was given a first GP drive in the first 81B in Austria and showed well despite considerable problems). The 81 continued in use into 1981; de Angelis scored with 81s three times before the 87 came and Mansell's first scoring finish came with one in Belgium.

Drivers: Mario Andretti, Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

An experimental dual-chassis car using an 81 monocoque. Completed in the Autumn of 1980 it was used for tests but never raced.

81 This actually appeared after the 88, and took the team place intended for that car in 1981. It was conventional, using 88 running gear - 88 to 87 (and vice versa) conversions were made in mid-season. A moulded carbon-composite monocoque was used. Some weight was saved in the second half of the season, and the 87B led directly to the 91.

Drivers in 87s scored 13 points in Lotus' 1981 total of 22, which as the team was in turmoil for much of the year was not at all bad. By the early summer-of that year the Team Lotus cars were black and gold again."The two 87Bs were used in the opening GP of 1982.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

Traditional Team Lotus pose with a new car - drivers Mansell and de Angelis flank Colin Chapman. The 87 still shows some allegiance to Essex (where the radiator air was exhausted through the sides) but in th~ maind1is is another )PS.

88 This wasrhe controversial 'dual-chassis' concept presented as a racewoi-thy car, entered for races, and rejected by officialdom. It had a main chassis comprising bodywork, carrying side pods and radiators, and aerofoils; within it there was the monocoque, engine and transmission, and suspension. The first chassis was carried on coil spring! damper units attached to the suspension uprights. The idea was to achieve generous ground effects downfoI"ce,. without the undue stress and strain drivers were having to bear with rock-hard ground effects suspension.

Protests forced it out of racing and it was modified as the 88B, which although acceptable to the RAC at the 1981 British GP meeting was not acceptable to anybody else in authority. Piles of paper marked its passing.

91 In many ways this might have been designated '87C', the prime objective being a stronger, and abQve all lighter, derivative of the 87. Lotus still used DFVs, so could not afford excess weight, and a very strong and rigid tub was achieved with a carbon fibre/Kevlar Nomex sandwich, weighing only just over 18kg. Suspension was very stiff, aerodynamic qu.alities good. Three wheelbase variations were built into the design, as was a controversial detail shared with other teams using DFVs - water-cooled brakes, which seemed to some to be an unnecessary weight. '

With this car Lotus went some way towards recovering competitiveness, most notably when Elio de Angelis won the Austrian Grand Prix. .

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

92 A pair of 91s converted to' comply with flat-bottom regulations for the opening races of the season, very much as stand-ins while the 93T was prepared. One was used in active suspension trials.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

93T Lotus' first turbo car was powered by the Renault EF4B V6, but as the team was pulled together under Peter Warr construction was sluggish, with only one car being available for the first Championship races. That was not the bad news it might have been, for the 93T was a cumbersome uncompetitive device, and as soon as Gerard Ducarouge joined as designer in the early summer of 1983 work starteq on a new car.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

95T Once again Team Lotus had a car that was instantly competitive, for although at the end of 1984 the best results were three third places, component failures or driver error had probably cost victories. However, third place in the Constructors' Championship was Lotus' best since 1978.

There was nothing revolutionary about the 95T, which was built around a carbon-composite monocoque with pullrod suspension, but it restored Lotus' old reputation for good handling. It was also more than a match for the works Renaults, and this was one factor that led to Lotus being favoured with better engines in 1985.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Nigel Mansell.

97T This car was a derivative, with aerodynamic refinements and Renault EF15 engines for races, delivering more power at some cost in reliability. There was strength in t!1e driver pair too - de Angelis finished 11 times in 1985, every time in a scoring position and with a victory at Imola, while Ayrton Senna finished nine times, winning in Portugal and Belgium. Lotus was again third in the Constructors' Championship.

Drivers: Elio de Angelis, Ayrton Senna.

98T Although this car appeared to be a straight successor to the 97T, Ducarouge departed from previous practice in using a one-piece moulded carbon-composite chassis. While the front suspension w~ carried over from 1985 there was a new set-up at the rear, used for most of the year's races, and an hydraulic adjustable ride height system was used! in conjunction with this. Renault made works-prepared EF15B engines available - other teams using the v-6 were supplied by the Mecachrome preparation company - and the higherrevving pneumatic valve operation type was sometimes used.

As was becoming customary, four cars were built. Lotus was actually in contention for the Championships for much of the year, eventually taking third place again on the Constructors' points table. Attention tended to focus on Ayrton Senna, who scored points ten times and won two Grands Prix; team mate Johnny Dumfries occupied the number two seat.

Drivers: Johnny Dumfries, Ayrton Senna.

99T The outward change was the adoption of yellow and blue Camel colours - that apart, the family resemblance was strong. Under the skin, however, there was a Honda 80-degree v-6 and many more ancillaries than with the Renault engine; there was also a Lotus six-speed gearbox, and active suspension. Although the car was tested with a revised 'normal' suspension arrangement, Senna was insistent on the active system, and he was a power in the team. Thus the 99T became the first Fl car to race with active suspension, in the Brazilian GP, and the first to win with it (at Monaco). Shortcomings in aerodynamics led to a substantial summer redesign, primarily to clean the airflow to the various rea1- wings used, while there was also criticism of the chassis.

This time six cars were built, three for R & D use in Britain and Japan. Lotus was third in the Constructors' Championship and Senna third in the Drivers' Championship, having scored in; 11 races and again having won two Grands Prix.

Drivers: Satoru Nakajima, Ayrton Senna.

lOOT Lotus slipped badly in 1988. The car looked rJght, with the needle~nosed lines adopted by most designers as a regulation requiring drivers' feet to be behind the centre line of the front wheels came into force, and it had an apparently competent 'passive' suspension system, as Twell as the advantage of Honda power. Fiddling with aerodynamics, track, wheelbase and so on brought little improvement in fortunes -.best placings were thirds, scored by Piquet in the first races of the season (at Rio and Imola) and in the final race at Adelaide. He was sixth in the Championship, and while Lotus slipped only one place on the Constructors' points table, the team's score was little more than a tenth of Mclaren's.

Drivers: Satoru Nakajima, Nelson Piquet.

101 Technical direction was taken over by 'Frank Dernie, whose recent reputation was as an aerodynamicist - he perhaps tended to be more concerned with that aspect than with, say, suspension. That comprised double wishbones, pullrod at the front, pushrod at the rear, with the front springs in blisters low on the sides of the hull and those at the rear fitted in neatly ahead of the Lotus longitudinal six-speed gearbox. The car was slim at the nose, widening at the cockpit to lines which followed through along the fuel cell and engine areas. For a normally-aspirated engine, Lotus looked to the Judd CV 90-degree V-8 and there,was some fuss early in the year about exclusive Tickford developments including a fivevalve head, which did appear briefly and soon disappeared. By the end of the year one of the,cars was being tested with a Lamborghini V-12 in preparation for the 1990 102.

This car was an improvement on Ducarouge's last Lotus, but some of its promise was illusory and some was dissipated the number one driver seemed demotivated for part of the season. At the Belgian GP meeting neither car qualified, and that was a low poin~ first in Lotus Grand Prix racing history. Piquet salvaged something with two fourth placings and two other points-scoring finiShes, while in his last race for the team Nakajima achieved his best result, fourth in Adelaide.

Drivers: Satoru Nakajima, Nelson Piquet

Author: ArchitectPage

Stirling Moss during a classic drive in Walker's blue 18 at Monaco in 1961 when he beat the much more powerful Ferraris in the first Championship race of the 1.5-litre Formula.

The slippery virtues of the 41 body must in large part have been offset by all those suspension bits and pieces upsetting the airflow.

The 93T looked a bulky car, and it proved ineffectual. The relationship with Pirelli was short-lived.